Summary

• There is strong global evidence that the Covid-19 pandemic has prompted a major increase in gender based violence (GBV). Pakistani women are at high risk and highly vulnerable to violence.

• Health crises, economic stress and containment measures (such as isolation and quarantines) all have an adverse impact on household management and interpersonal relationships, compounding issues like domestic abuse, mental health, care for the elderly and exacerbating existing gender inequalities.

• With economic uncertainty, informal jobs, which account for most women’s employment, have been the first to go and some of the economic and social gains women have fought so hard to obtain may be lost.

• Improving women’s financial autonomy, robust public communications that target GBV, and providing free and easy-to-reach resources for at-risk women are all immediate policy measures that must be integrated into the government’s wider Covid-19 response.

Identifying the Problem

Gender Based Violence (GBV), particularly domestic violence, is a phenomenon that increases during crisis situations and emergencies – whether natural disasters, economic crisis, wars and conflict or disease outbreaks [i].

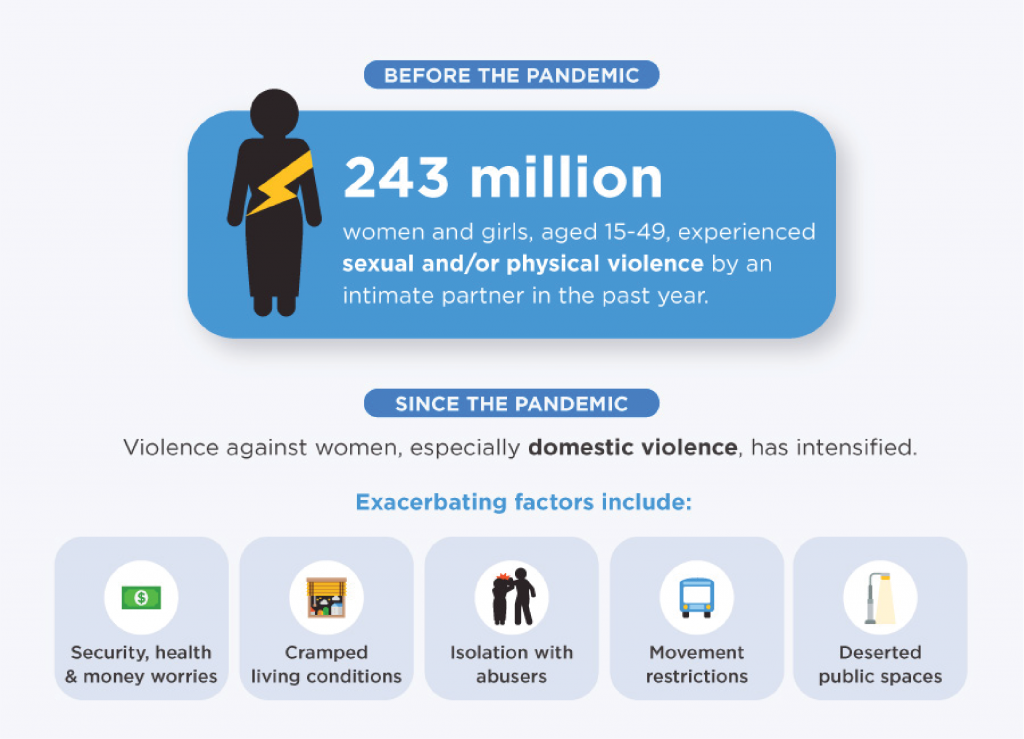

Figure 1 illustrates the pre-existing problem of GBV and the factors that contribute to its aggravation. The UN has referred to the looming crisis of GBV as a ‘shadow pandemic [ii]’ with serious ramifications for the safety, protection and health of women. A recent report by UN Women titled ‘The First 100 Days of Covid-19 Outbreak in Asia and the Pacific: A Gender Lens’ discloses that the pandemic has a disproportionate effect on women and girls [iii].

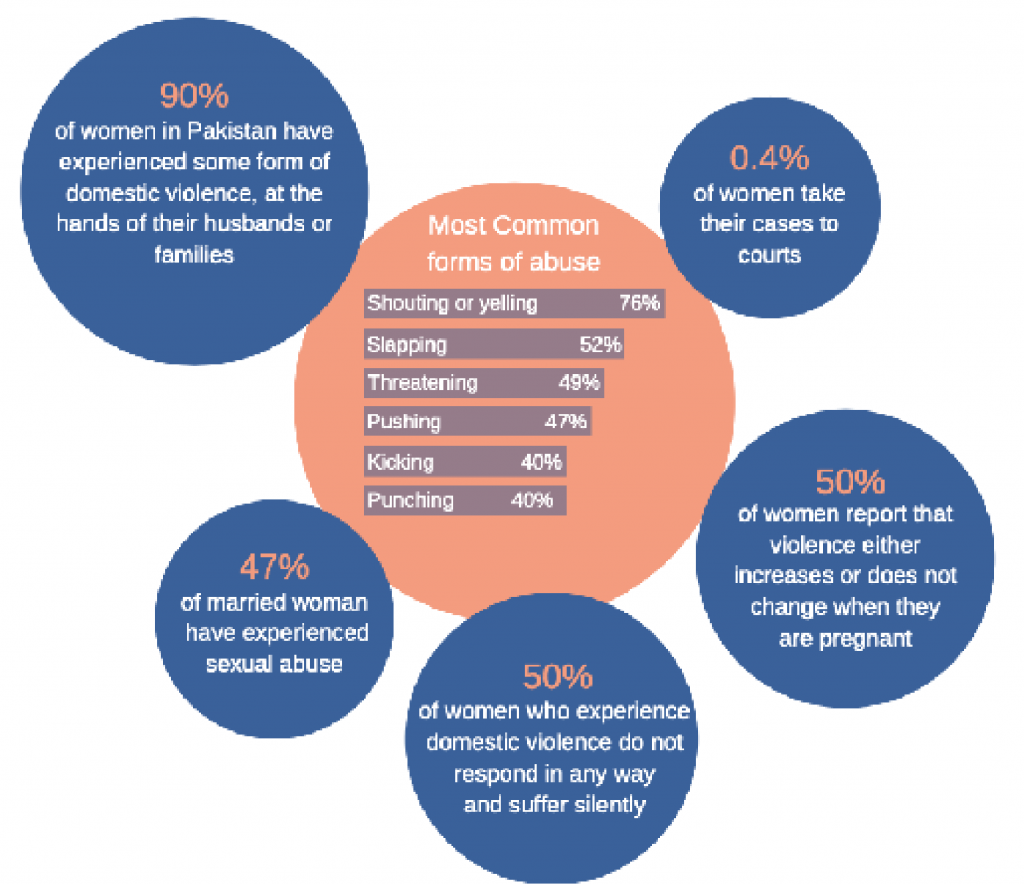

According to UNFPA, the health and socio-economic stress generated by pandemics often results in a collapse of social infrastructures, therefore, compounding existing gender inequalities and toxic social norms [iv]. As per Global Gender Gap Report 2020, Pakistan is ranked second lowest on gender parity, and fares poorly when it comes to women’s education, financial inclusion, employment and legal representation [v]. Pakistan’s ranking on the Gender Parity Index (GPI) is especially worrying considering global evidence that violence against women has been on the rise since the outbreak of Covid-19 [vi]. While official data on GBV, specific to Pakistan, during the pandemic does not exist as of now, existing data on GBV pre-Covid and anecdotal evidence paints a grim picture.

Containment measures such as social isolation and restricted movement have led women to observe a ‘lockdown’ at home, increasing their vulnerability to domestic violence, with little access to help and support. The situation is exacerbated by the housing situation in Pakistan where 68% of all housing units have either one or two rooms [vii].

Institutional mechanisms in place for response, prevention and protection are under pressure both in terms of outreach and access. Helplines are non-operational and the number of existing shelters is inadequate for the rising number of GBV cases [viii].

What exacerbated the problem?

Women’s reduced financial autonomy, coupled with their confinement at home as a result of job losses and suspensions, increases their vulnerability to domestic violence. In Pakistan and world over, the resulting economic uncertainty from the pandemic has had a dire impact on the financial situation of households:

- Informal jobs which account for most women’s employment have been the first to go. Over a quarter of Pakistani women have been fired or suspended from their jobs in various sectors.

- Women in the formal sector are concentrated in the service economy which has been the worst hit by Covid-19 [xi].

- As women lose jobs, it exacerbates their economic fragility. Restricted access to financial resources and limited involvement in financial decision making makes it harder for women to leave perpetrators of violence.

- The heightened pressure felt by men to provide for their families and their inability to do so is a factor that contributes to GBV, specifically intimate partner violence.

- School closures exacerbate the problem as women have to stay home to perform care and domestic work. This also means that the girl child is more vulnerable to abusive situations.

Patriarchal norms dictate that GBV falls under the ambit of the private domain of family as opposed to the public domain that the State has to address through disaster management policies. Essentially, what this means is that while the government focuses on the health and consequent economic crisis generated as a result of the pandemic, GBV has been deprioritized at a time when it needs more recognition.

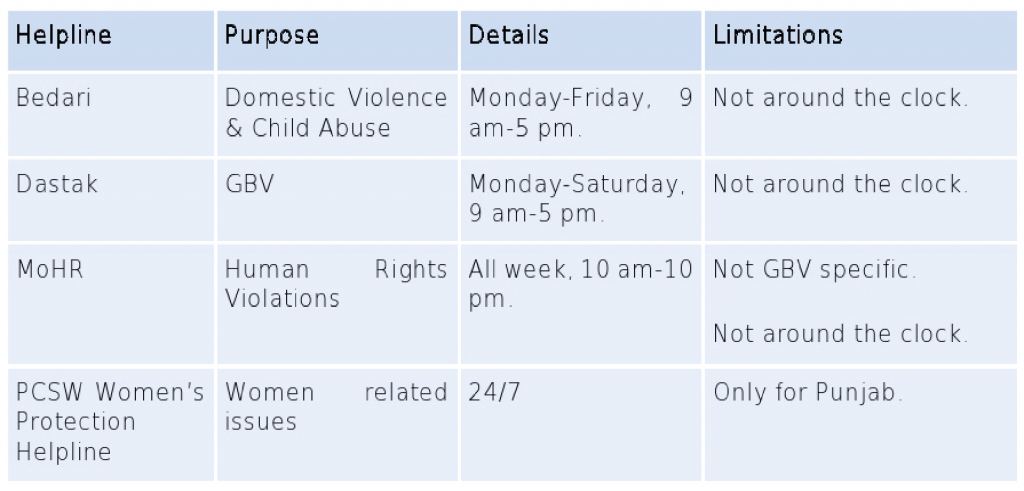

GBV helplines have their own limitations as shown in the table below. Most helplines are not functional around the clock, and the call back option can gravely endanger the life of a woman. The MoHR (Ministry of Human Rights) helpline broadly addresses issues of human rights as opposed to specializing in GBV related issues. This poses the risk of victims of GBV not getting the required support as staff is not specifically trained to provide support to victims and address issues related to GBV. Similarly, Punjab Commission on the Status of Women’s helpline is restricted to Punjab and does not extend its services to other provinces. Helplines launched by NGOs like Dastak and others have seen an exponential rise in complaints, making it difficult to manage the situation [x]. Close proximity to abusers due to lockdowns and layoffs makes it increasingly difficult for women to call helplines and seek help. Women, especially in remote and rural areas have little access to personal mobile phones, making it harder to access these services.

State run shelter homes or Dar ul Amans are few in number and are only available at district levels, making it difficult for women from far flung areas to access these facilities [xi]. The residential capacity of these shelters is also very low, averaging at 20 persons a time. Admission into these facilities has become harder during the Covid-19 pandemic as women are required to provide negative PCR tests that are costly, along with a court or police order that are sometimes difficult to obtain. Women are also less likely to file complaints and access protection facilities due to existing taboos around women reporting a crime of violence especially if it’s intimate in nature or orchestrated by a family member.

Recommendations

1

GBV Awareness

Due to the surge in GBV cases, a ‘women’s emergency’ should be declared, supplemented with a government led targeted aggressive awareness and advocacy campaign against GBV across all mediums especially TV and radio. In doing so, the state will reframe the issue of GBV from a private family matter to a public one requiring state intervention and attention. The awareness campaign should:

• Discourage GBV against children, women, trans and persons with disa-bilities.

• Encourage women to speak up against GBV and seek help.

• Provide information on support mechanisms, e.g. helplines and shelter facilities.

• Recognize the increased caregiving responsibilities of women.

• Encourage men and boys to challenge gender inequalities and stereo-types.

2

Access to

Support

GBV should be factored into the Covid-19 response, with specific fund allocation. GBV support should be declared an essential service during Covid-19 to ensure that resources aren’t redirected to other areas of concern.

Funds should be allocated to increasing the capacity of existing shelters and establishing more on the district and sub-district level. The service delivery capacity of shelters should be increased especially for provision of medical supplies. Welfare and psycho-social support should be ensured at these facilities. Moreover, police or other helplines should be directly linked to shelters to ensure a quick response time. Legal and administrative barriers to accessing these shelters should be eliminated.

3

Economic

Vulnerability

and Financial

Autonomy

Government outreach and financial assistance programs should be designed to protect the livelihoods of women, improve women’s empowerment, reduce unequal burden of care, as well as GBV. These programs should offer support to individuals, home based, and SMEs to ensure women have access to financial resources. Urgent cash assistance interventions should exist for women at risk and undergoing GBV.

This material has been developed by Tabadlab in partnership with DRI. It has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

End Notes

[i] UNFPA. (2020, March 20). As Pandemic Rages, Women and Girls Face Intensified Risks.

[ii] UN Women. (2020, May 27). ‘The Shadow Pandemic: Violence against Women during Covid-19’. Press Release.

[iii] UN Women. (2020). The First 100 Days of the Covid-19 Outbreak in Asia and the Pacific: A Gender Lens.

[iv] UNFPA. (2020, March 20). As Pandemic Rages, Women and Girls Face Intensified Risks.

[v] World Economic Forum. (2020). Global Gender Gap Report 2020.

[vi] Feroz, N. (2020, April 9). Domestic Violence Amid Corona Pandemic is Increasing Manifold. Naya Daur.

[vii] Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Housing Units by Number of Rooms and Type.

[viii] Quresh, U. (2020, June 9). Women and Girls must be at the Center of Pakistan’s Covid-19 Recovery. World Bank Blogs.

[ix] Ebrahim, Z. (2020, December 1). ’Moving Mountains’: How Pakistan’s ‘invisible’ Women Won Workers’ Rights. The Guardian.

[x] Bari, M. (2020, July 7). Pakistani Women Trapped between Coronavirus and Domestic Violence. DW.

[xi] Information in this paragraph has been obtained through an interview with Fauza Yazdani who is a Development Consultant and Policy Advisor on issues of gender.