Summary

• Enclosed and crowded spaces are hot spots for the spread of virus, particularly with lack of social distancing, ventilation and people not wearing masks. Studies show that masks can reduce the relative infection rate of the virus by 65-75%.

• While the usage of masks has been mandatory since the end of October 2020, implementation remains significantly compromised. Mask fatigue is clearly visible and perceived reduced risk of the virus and a failure of effective crisis communication have all contributed to lack of implementation.

• Public officials and other persons of influence must lead by example and wear masks to enhance general level of compliance with the same.

• Renewed focus on containment measures is required within the overall crisis communication. Promote mask-wearing as part of the social contract, i.e. responsibility for collective health.

• In order to improve accessibility of masks for low income groups, innovative alternatives such as homemade masks made along the guidelines provided by World Health Organization (WHO) can be encouraged.

The Problem

As the second wave of Covid-19 persists, the usage of face masks in public spaces, on transport and in schools, offices and wedding halls has been made mandatory by the National Command and Operation Centre (NCOC) as of October 28th, 2020 [i]. Whilst scientific evidence on the absolute utility of masks as an infection control method in the case of Covid019 is still patchy, studies conducted so far have found that masks can reduce the relative infection rate of the virus by 65- 75% [ii]. Furthermore, the WHO recommends mask-wearing where a distance of at least 1 metre cannot be maintained as a component of a comprehensive strategy for the prevention of the spread of Covid-19 [iii]. Despite these guidelines and the NCOC’s formal institutionalization of mandatory mask-wearing policies, compliance continues to be an issue in the country.

Prior to the NCOC’s decision for mask-wearing as a mandatory policy, provinces had been asked to ensure compliance with non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) detailed in the visual below in cities and districts where positivity rates exceeded 2%, such as Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad. To this end, local administrations introduced a variety of fines and stipulations for arrest in the event of noncompliance, but anecdotal and surveyed evidence indicates mask-wearing is not widely practiced. The second wave, in particular, has seen even lower levels of compliance. Whilst noncompliance was fined rigorously by the administration during the first wave, the same level of seriousness is not demonstrated this time around.

Noncompliance is especially an issue in enclosed and crowded spaces, such as mosques, markets, public transport and schools and other mass gatherings. In these cases, the WHO recommended social distancing of at least 1 metre is often unachievable, thus turning these locations into hubs for the spread of the virus when masks are not donned. While schools were closed for a second time from November 2020 to January 2021, other public gatherings particularly weddings have been in full swing, which are potential hot spots for the spread of virus. Outdoor events were limited in November 2020 but still allowed up to 500 attendees in most instances, with variation in this number across provinces [iv].

Factors Exacerbating the Problem

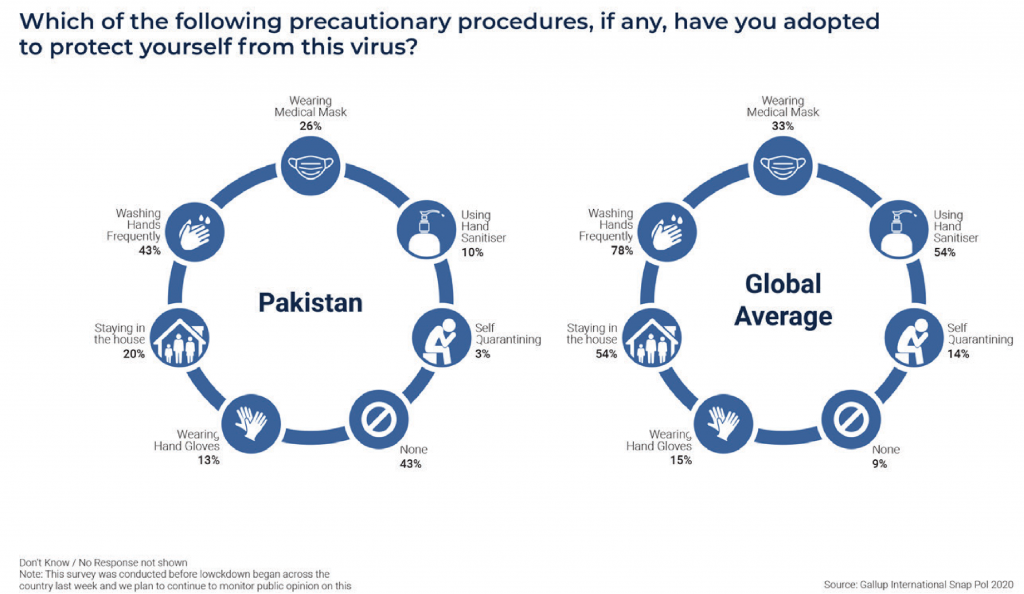

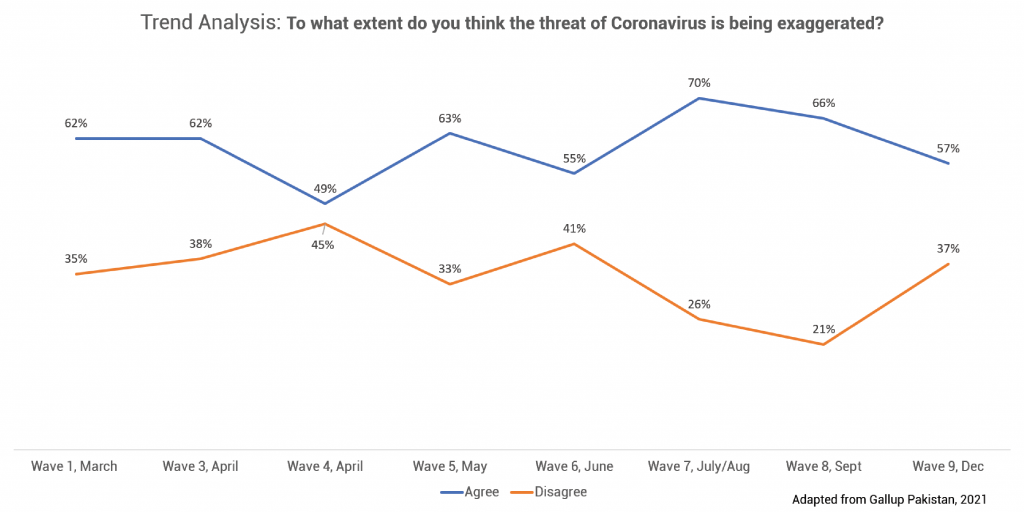

There is a plethora of psychosocial circumstances that exacerbate this problem, some unique to the Pakistani case and some global. Generally, the term “mask fatigue” encapsulates a range of biomedical and psychosocial reasons because of which people refrain from wearing masks or from wearing them for an extended period of time, including respiratory compromise, headaches, anxiety, and reduced social interaction. Additionally, due to the impression that Pakistan was not as badly affected by the virus during the first wave as was projected, the perceived risk of Covid-19 has significantly reduced and effective crisis communication has been compromised. As a result, compliance with mask-wearing policies has dipped even further, the reasons behind this supported by some early non-peer review research that has found a lack of perceived risk can cause decreased adherence to preventive measures [v]. In fact, a significant majority (close to 60%) of the population believes that the risk of the virus is exaggerated.

A field-based interview with Karachi residents by a news channel [vii] is telling of the variety of skeptical opinions on mask-wearing in the general public: some people did not believe in the authenticity of the Covid-19 threat altogether and believed it is a conspiracy theory (this is corroborated by evidence found in an academic study that 46% of people in Pakistan believe Covid-19 is a bioweapon); some people believed not wearing a mask indicates bravery in facing the threat; some people understood the need for masks but did not wear them in social settings due to peer pressure; and others only wore masks when absolutely necessary, removing them at other times.

Selective mask-wearing is further exacerbated by the fact that current measures, such as fines for noncompliance, are only applicable to outdoor settings. In order to tackle mask-wearing in indoor spaces, awareness is key. Moreover, information regarding the importance and technique of wearing masks is asymmetrically distributed across the country

Implications

According to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), [viii] the effectiveness of mask usage in community settings is realized when everyone wears a mask by preventing the spread of the Covid-19 virus through respiratory droplets that are released when talking, sneezing, or coughing. According to studies, approximately 50% of these transmissions happen from people who are asymptomatic carriers of the virus. Due to a lack of awareness of the above, masks are not currently being used as an effective infection-control strategy.

There was an increase in cases throughout the months of November and December, with over 2,000 cases and approximately 50 deaths being recorded every day [ix]. Furthermore, the positivity rate has also increased from 2% in mid-October and 3% at the end of October to around 5% as of the writing of this brief. The Special Assistant to the Prime Minister on Health, Dr. Faisal Sultan, has attributed this rise to people not following SOPs. It is also worrisome to see that deaths as a percentage of cases was the highest at 3.7% at the end of December 2020, making the use of prevention tools all the more important.

With overcrowding in enclosed spaces such as buses, offices, markets and mosques now that the economy has opened up, the chances of virus spreading are higher. Moreover, in the initial period, the Covid-19 was largely seen to be an urban phenomenon. However, with passage of time, it may spread to other areas as well, as may already be happening and containment will become a bigger challenge in such a scenario, particularly with health facilities not consistently available across the length of the country.

Pakistan’s existing healthcare system is ill-equipped to deal with the kind of spread of the virus witnessed elsewhere in the world, and can be easily overwhelmed. Should mask-wearing policies, together with other NPIs, fail to be effectively implemented, the government will have to reconsider the possibility of a lockdown, as many states in the Global North have. In the context of Pakistan, however, this will again raise a precarious debate on lives versus livelihoods. With a large low-income and daily-wager population, lockdowns as a containment measure do not come without grave risk of their own. Children are also beginning to return to schools and in such a time, ensuring masks are worn by everyone is increasingly important.

Pakistan expects to start its vaccination drive in March 2021, though only 1.1 million vaccines are expected in the first phase, and no orders have been placed as of yet. Furthermore, even if Pakistan receives the expected 45 million doses of the UN’s Covax vaccine, the timing of which is highly uncertain, this will only cover 20% of the population [x], a far cry from the 55-82% required to achieve herd immunity. Until this is achieved, masks will remain an essential containment strategy. Moreover, as the vaccines are progressively administered over time, containment measures will remain essential in ensuring Pakistan’s healthcare system has the capacity to move towards cure. Continually rising cases will not only overwhelm the system but might also discourage people from visiting healthcare centers and can prove to be detrimental to the efforts directed at the nation-wide vaccination drive.

Finally, if messaging regarding the virus and masking is not made clear and direct to the general population, persisting skepticism regarding the threat of the virus and the effectiveness of mask-usage will further reduce the number of people who abide by this SOP in the long-run, leading to spikes in the local transmission rate in the future. Whilst mask-wearing is insufficient to contain the virus in isolation, it is an essential component of a comprehensive strategy to secure the country’s public health at this time.

Recommendations

1

Renewed Focus on Crisis Communication

• Use a range of digital and offline media channels to spread awareness to different segments of the population.

• Mask-wearing should be presented as a strategy to protect communities as opposed to individuals. Promote mask-wearing as part of the social contract, i.e. responsibility for collective health.

• Collaborate with grassroot organizations for community-led awareness campaigns.

• Engage local religious leaders, cultural influencers, and health workers with local ties to help with crisis communication.

• Explore other channels of communication such as public transport, trucks, and billboards to ensure maximum penetration

2

Introduce Innovative Alternatives in order to Improve Accessibility

• Homemade masks made along the guidelines provided by WHO can be effective infection-control measures in the event that surgical and N-95 masks are unavailable or inaccessible. Awareness regarding how to make these should be spread.

• This will partly address the issue of affordability and inaccessibility of masks for low-income households.

• Encourage the public to repurpose existing pieces of garment, such as chaadars, dupattas, and handkerchiefs into face coverings when around others.

• Engage local communities during awareness campaigns to take charge of producing low-cost masks for their communities.

3

Lead by Example

• Public officials and other persons of influence must lead by example and wear masks to enhance general level of compliance with the same.

• Parliamentarians at the national and provincial levels should use social media and offline methods to promote mask-wearing in their local constituencies.

• Regulate mask-wearing at all other levels of leadership. TV presenters, Imams of local masjids, local retailers and healthcare providers should be required to comply with the policy strictly so that social pressure working against wearing of masks can be reversed.

• Mask-wearing should be mandated and monitored in local capacities, such as individual offices, mosques, shops and meetings via all levels of leadership engaged.

This material has been developed by Tabadlab in partnership with DRI. It has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

End Notes

[i] Andolu Agency (2020, October 29). Pakistan makes masks mandatory as virus cases climb.

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/

[ii] Chu, D. K. et al. (2020). Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31142-9/fulltext & Turak, N. (2020, May 19). Wearing a mask can significantly reduce coronavirus transmission. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/05/19/coronavirus-wearing-a-mask-can-reducetransmission-by-75percent-new-study-claims.html

[iii] WHO (2020). Mask use in the context of COVID-19.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/advice-on-the-use-ofmasks-in-the-community-during-home-care-and-in-healthcare-settings-in-the-context-of-the-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)-outbreak

[iv] Latif, A. (2020, November 11). Pakistan: COVID-19 cases continue to surge. Andolu Agency.

https://www.aa.com.tr/en/latest-on-coronavirus-outbreak/pakistan-covid-19-cases-continue-to-surge/2039790

[v] Habersaat, K. B. et al. (2020). Ten considerations for effectively managing the COVID-19 transition. Nature Human Behaviour.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-020-0906-x

[vi] Gallup Pakistan (2020). Coronavirus Attitude Tracker Survey Pakistan.

https://gallup.com.pk/post/30619

[vii] Shaid, U. (2020, November 30). Here’s why some Karachiites don’t wear masks. Samaa.

https://www.samaa.tv/news/2020/11/heres-why-some-karachiites-dont-wear-masks-in-public/

[viii] CDC. (2020). Considerations for wearing masks.

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html

[ix] Government of Pakistan’s COVID-19 portal.

https://covid.gov.pk/

[x] Malik, M. (2021, January 11). Coronavirus: Pakistan’s efforts to procure vaccine will cover just 20pc population. Dawn News.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1600833/coronavirus-pakistans-efforts-to-procure-vaccine-will-cover-just-20pcpopulation