IMF approves $6 billion Extended Fund Facility (EFF)

Sayem Z. Ali

An e-reader friendly version of this can be downloaded here.

On July 3rd, 2019, the IMF board approved a US $6 billion Extended Fund Facility (EFF) for Pakistan. The three-year EFF was approved after the government implemented a number of prior actions that were agreed between Pakistan and the IMF in the staff agreement in May 2019. These actions included a radical overhaul of tax policy, an increase in gas & power tariffs for cost recovery and a market-based monetary & exchange rate regime to rationalize imports, serve as buffer against external shocks and build up the depleted foreign exchange reserves. The IMF and government officials agreed that these measures were necessary to tackle an unsustainable build-up in the level of public debt & liabilities.

Instituting these measures has been politically challenging for the still relatively young elected government of the Pakistan Tehreek Insaf (PTI) led by Prime Minister Imran Khan. Anticipating a public backlash against the rising cost of doing business and higher cost of living, the PTI government spent nearly a year pushing back on Fund staff conditions that it deemed too stringent. It also sought alternative solutions to shore up Pakistan’s external finances. The government and the IMF staff finally reached a staff level agreement on the pace of the macro adjustment in May 2019—but after much upheaval within the government, with the resignation of the finance minister, as well as several months of detailed and tense technical deliberations between Pakistani and IMF officials.

Avoiding the hard landing & limiting the quantum of adjustment

Short term pain is inevitable. The IMF forecasts GDP growth to from 3.3% in FY19 to 2.4% in FY20. Inflation (CPI) will rise from 7.3% to 13%. But recovery may not take as long as many analysts think. The biggest reason to be hopeful is the manner in which the measures taken have helped avoid a “hard-landing”.

| Table 1: Economic Outlook FY20 to FY23 | |||||||

| FY18 | FY19 | FY20 | FY21 | FY22 | FY23 | ||

| (forecasts) | |||||||

| Real GDP growth | % | 5.2 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| CPI Inflation | % | 3.9 | 7.3 | 13.0 | 8.3 | 6.0 | 5.0 |

| Nominal GDP | Rs bn | 34,396 | 38,559 | 44,003 | 49,568 | 55,380 | 60,918 |

| C/A deficit | % GDP | -6.4 | -4.7 | -2.6 | -2.0 | -1.8 | -1.7 |

| Primary deficit | % GDP | -2.2 | -1.8 | -0.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| Public Debt | % GDP | 75.7 | 77.7 | 77.6 | 75.0 | 71.0 | 70.0 |

| Source: Medium Term framework FY20 Budget documents and IMF staff forecasts | |||||||

A hard landing refers to a marked economic slowdown or recession following a period of rapid growth. The most recent experience of the economy with a hard landing was in response to the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, when real GDP growth collapsed to 0.4% and inflation shot up to 19.6%. It took half a decade to recover from that hard-landing, as the annual growth rate averaged 2.8%, compared to 6.5% in the five years preceding the hard landing).

The 2019 IMF-supported adjustment is not likely to take as long to recover from. Growth could return surprisingly quickly as the quantum of adjustment (in real terms) is smaller than in previous IMF programmes.

| Table 2: Quantum of Adjustment agreed under the IMF programme | |||||||||

| FY08 | FY09 | Change | FY13 | FY14 | Change | FY19 | FY20 | Change | |

| Real GDP | 5.0 | 0.4 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 2.4 | |||

| CPI Inflation | 12.0 | 19.6 | 7.4 | 8.6 | 7.3 | 13.0 | |||

| Primary deficit | -2.9 | -0.2 | 2.6 | -3.9 | -0.3 | 3.7 | -1.8 | -0.6 | 1.2 |

| Current Account deficit | -8.1 | -5.5 | 2.6 | -1.1 | -1.3 | -0.2 | -4.7 | -2.6 | 2.1 |

| Source: IMF WEO 2018 and IMF press release July 2019. | |||||||||

The scale of adjustment is significant in nominal rupee (PKR) terms, but in real terms (% GDP) the adjustment is smaller than previous programmes. This means that there will be less tightening of monetary and fiscal policy than under previous IMF programmes. The lower size of the adjustment will mitigate the drag on growth and limit the impact of inflation.

The quantum of adjustment is lower than under previous IMF programmes for five reasons:

- The shift to a market-based exchange rate

- The gradual transition of energy prices to the level of cost recovery

- The overhaul of tax revenue as the primary instrument for fiscal adjustment

- The restructuring of public debt to enhance fiscal space

- The access to approximately US $38 billion in external funding from other countries

Each of these factors are explained in greater detail below.

- The shift to a market-based exchange rate

The biggest economic challenge facing the government was the unsustainable build up in the current account deficit. Fuelled by an overvalued exchange rate, it grew to US $19.9 billion or 6.3% of GDP June 2018. When the new government took oath in August 2018, it was forced to seek extraordinary external funding to avert a default on debt. Going to the IMF immediately would have required a much higher upfront adjustment in the exchange rate as well as the interest rates, so that the deficit could have been reduced from 6.3% to 2.6%. This would have produced the very definition of a hard landing for the economy.

Instead the government chose to phase this adjustment out over a much longer period of time, with the current account deficit projected to close at US $13 billion (or about 4.7% of GDP) in FY19, down from 6.3% in FY18. The longer adjustment period that this afforded the private sector meant that businesses could better hedge against the risk of devaluation and the rising cost of credit. In combination with this pre-IMF programme adjustment carried out by the government was the nearly US $9 billion in foreign assistance from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and China in FY19.

In short, with the bulk of the adjustment having already taken place, the government has managed to establish a trajectory on which the current account deficit will fall to US $10.5 billion in FY20. Another US $3 billion in deferred oil payments from Saudi Arabia will come online that year, effectively allowing Pakistan to achieve the IMF’s current account deficit target of US $7 billion for FY 20, without a further adjustment in the exchange rate.

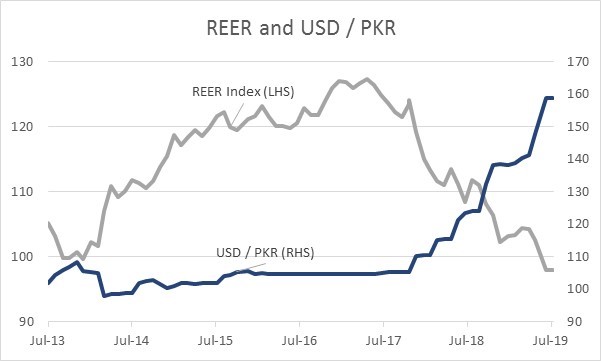

From the Real Effective Exchange rate (REER) perspective, that measures the competitiveness of the Pakistani rupee against its top 20 trading partners, the index has moved from showing that PKR is overvalued in 2017 to reaching near equilibrium (102) in May 2019. Since then the nominal exchange has depreciated 8%, and the REER index will likely decline to 98 by June 2019. This is the lowest level recorded since December 2013 and underlies that the Pakistani rupee has regained its competitiveness.

From the Real Effective Exchange rate (REER) perspective, that measures the competitiveness of the Pakistani rupee against its top 20 trading partners, the index has moved from showing that PKR is overvalued in 2017 to reaching near equilibrium (102) in May 2019. Since then the nominal exchange has depreciated 8%, and the REER index will likely decline to 98 by June 2019. This is the lowest level recorded since December 2013 and underlies that the Pakistani rupee has regained its competitiveness.

However, maintaining the rupee’s competitive will require the nominal exchange rate to adjust for the inflation differential between Pakistan and its top trading markets. Hence, an adjustment of 9% is expected in FY20, and as inflation declines, the quantum of adjustment in the nominal exchange rate will also decline.

- Energy prices are almost at cost recovery

Another key factor in preventing a hard landing for the economy has been the tariffs increases for power & gas companies to bring the rates closer to full cost recovery. From July 01 2019, power tariffs were raised by 12% and gas tariffs were raised by 28% to bridge the growing losses of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs). In FY18, the losses had ballooned to around Rs 577bn (1.7% of GDP), reducing only marginally in FY19 at 1.3% of GDP.

| Table 3: Losses of power sector SOEs (Rs bn) | ||||||||

| FY13 | FY14 | FY15 | FY16 | FY17 | FY18 | FY19p | FY20p | |

| Gas utilities | 26 | 5 | -22 | -37 | -66 | -146 | -110 | -30 |

| DISCO net profits | -20 | 14 | -72 | -128 | -137 | -253 | -190 | -90 |

| DISCO tariff subsidy | -345 | -288 | -181 | -136 | -163 | -179 | -209 | -217 |

| Total DISCO losses | -366 | -275 | -253 | -264 | -300 | -431 | -399 | -307 |

| Losses of Power SOEs | -340 | -270 | -275 | -301 | -366 | -577 | -509 | -337 |

| % GDP | -1.5% | -1.1% | -1.0% | -1.0% | -1.1% | -1.7% | -1.3% | -0.8% |

| Source: Calculations based on numbers reported by Ministry of Power and SNGPL, SSGC. | ||||||||

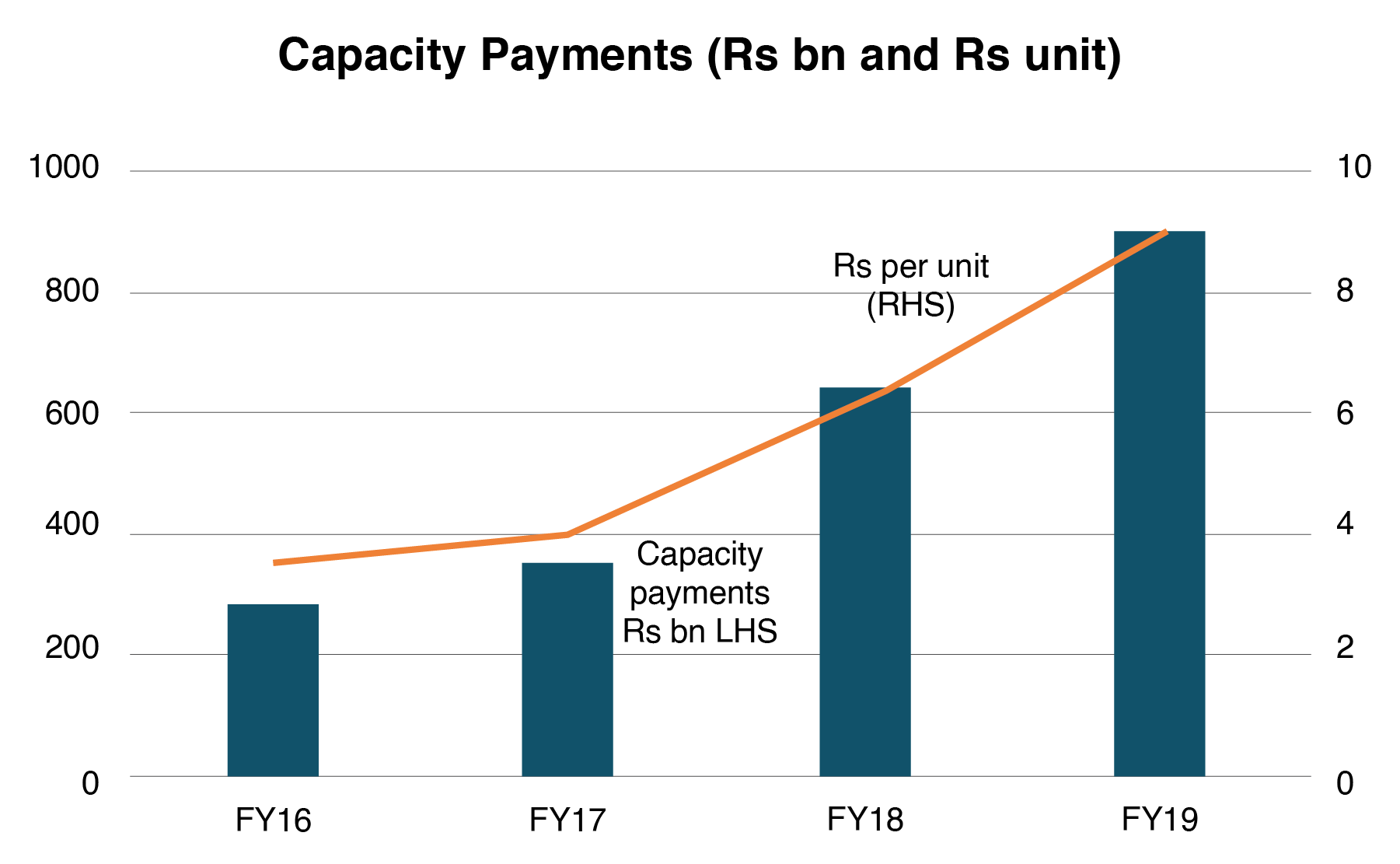

Power sector losses have continued to pile up as new power projects come online, adding to the capacity payments which are estimated to have ballooned to over Rs 900bn in FY19 (Rs 9 per unit of power generated). In FY16, the total capacity payments were Rs 280bn (Rs 3.4 per unit). This massive increase in capacity payments is the primary reason for the 12% hike in tariffs to Rs 12.7/unit and is now the biggest contributor to the circular debt.

There is no doubt that these increases in tariffs tend to have an inflationary impact, especially on the poor and vulnerable. The government has sought to cushion  citizens by carefully structuring the tariff increases in a manner that minimizes the impact. 78% of domestic electricity consumption will not face higher prices. Unlike Pakistan’s two previous IMF programmes, which forced tariff revisions in categories for consumers of less than 300 units, the government negotiated a subsidy for its most vulnerable citizens.

citizens by carefully structuring the tariff increases in a manner that minimizes the impact. 78% of domestic electricity consumption will not face higher prices. Unlike Pakistan’s two previous IMF programmes, which forced tariff revisions in categories for consumers of less than 300 units, the government negotiated a subsidy for its most vulnerable citizens.

The government has negotiated retaining subsidies for exporters and agriculture tube wells. These are now locked in for the next eighteen months, although quarterly fuel price adjustments will continue to be passed on to consumers.

The gas sector is facing similar challenges with more expensive LNG accounting for 25% of all gas supply in FY19, from zero in FY17. Given the energy mix, this has resulted in costs going up significantly over the last three years.

| Table 4: Gas tariffs by consumption slabs (Rs per MMBTU) | |||||||

| Gas Tariffs | Cost recovery (%) | Tariff increase | |||||

| Consumption slab (HM3) | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2019 0ver 2018 |

| 1. (up to 0.5) | 110 | 121 | 121 | 18% | 19% | 16% | 0% |

| 2. (up to 1.0) | 110 | 127 | 300 | 18% | 20% | 41% | 136% |

| 3. (up to 2.0) | 220 | 264 | 553 | 36% | 42% | 75% | 109% |

| 4. (up to 3.0) | 220 | 275 | 738 | 36% | 44% | 100% | 168% |

| 5. (up to 4.0) | 600 | 780 | 1107 | 99% | 124% | 150% | 42% |

| 6. (above 4.0) | 600 | 1460 | 1460 | 99% | 232% | 198% | 0% |

| Average weighted tariff | 390 | 540 | 691 | 64% | 86% | 94% | 28% |

| Break even cost | 608 | 630 | 738 | 17% | |||

| Source: SNGPL notified tariffs | |||||||

Effective July 01, 2019, the government has notified a 28% increase in average tariffs for domestic consumers, even though the oil and gas regulator (OGRA) recommended a 37% increase. Again, the government sought to protect vulnerable citizens and industry. All consumers using less than 3HM3 (or 95% of all domestic consumers) will continue to enjoy subsidy, paid in part by higher end consumers that use more than 4HM3.

For the industry, the gas increase is estimated to range between 12% to 18%, this is after the impact of 50% reduction in GIDC is priced in. The fertilizer industry tariffs remain unchanged, whereas the export sector (zero rated industry) will continue to get gas at subsidized rates.

- Fiscal adjustment will be driven by a radical overhaul of tax revenues

The quantum of fiscal adjustment targeted in FY20 under the IMF programme is 1.2% of GDP, which is significantly lower than the two previous IMF programme adjustments (3.7% of GDP in FY14 and 2.6% in FY09). The 0.5% of GDP adjustment in the energy sector through tariff increases helps reduce the fiscal burden too.

A smaller fiscal adjustment is positive from a growth perspective and the FY20 budget targets a scale up in investment projects and social sector spending. Contrary to traditional austerity programmes, this government has sought to protect social sector spending by ring fencing increased funds for social protection and for parts of the country, like the newly merged districts of in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa that need enhanced investments.

The bulk of the fiscal adjustment, therefore, is not coming at the expense of the poor, but through increased tax revenues. FBR revenues are targeted to rise to Rs 5,550bn (12.6% of GDP), from an estimated collection of Rs 4,150bn in FY19 (11% of GDP). This is incredibly ambitious and will require a serious revamp of tax policy and administration. Policy statements from the head of the tax authority, the Federal Bureau of Revenue (FBR) indicate the serious intent on the part of the government.

Avoiding the easy allure of anti-growth measures like raising the GST to 20% or imposing super taxes on business, as was done in the previous regimes, the government has planned a radical overhaul in the tax regime. Nearly all the major exemptions for big business have been removed and the government has started a crackdown on undeclared assets. How long the government can resist the pushback from the business lobby and how strenuously it can continue to pursue tax evaders and those holding undeclared assets will be crucial to determining the success of its economic plans. A revenue target of 12.6% of GDP in Pakistan is a big question mark—and much will hinge on the ability of the authorities to meet it.

- Debt restructuring on public debt will give additional breathing space

Public debt increased from Rs 7.7 trillion in FY09 to over Rs 28.6 trillion in FY19, meaning that debt has nearly quadrupled in a decade. In the upcoming year, just the size of interest payments on the debt will reach Rs 2.9 trillion, which is a whopping 83% of the total budgeted federal revenue collection targeted in FY20 Budget (net of provincial transfers and inclusive of all tax and non-tax revenue).

This debt trajectory is not sustainable. The IMF staff debt sustainability analysis shows that debt restructuring is imperative. On the external side, debt servicing (interest payments) is projected to rise to 45.7% of total exports (goods & services) in FY20, compared to 22% in FY16. Over the course of the IMF’s three year programme, public debt maturities are projected at a whopping US $38 billion.

As part of the wider IMF programme, the government is almost certain to seek restructuring of most of the short-term liabilities it holds, including the deposits placed for one year with State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) by China, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and now Qatar. There is a likelihood that these liabilities will be moved to longer tenors (three years and above) to reduce the roll over risk on the country’s balance of payments.

Similarly, on the domestic debt the government is likely to restructure the short-term debt holding by the SBP into longer tenor bonds (3, 5 and 10 year PIBs). Government borrowing from the SBP has increased alarmingly over the last three years, and now stands at over Rs 7 trillion or about 38% of the total domestic debt of government. In contrast, at the end of FY16, government borrowing from SBP was at Rs 2.5 trillion or only 15% of domestic debt. Unlike previous IMF programmes where the government had to reduce their stock of SBP borrowing through commercial bank borrowing – this time around there is no such condition. The stock at the end of the IMF EFF is projected to remain at Rs 7 trillion. Instead the government has committed to zero net borrowing and to reschedule the SBP borrowing into longer tenor bonds.

This move will benefit the government through reducing the rollover risks, thereby reducing the size of auctions in the bond markets. A significant reduction in the auction size will force banks to lend to government at more competitive rates.

- External funding of US $38 billion

Going back to the IMF was inevitable. Pakistan external funding requirements over the next three years (FY20-FY22) stand at a mammoth US $81 billion, including about US $60 billion of debt repayments that are maturing before June 2022. The current State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) FX reserves are grossly inadequate to cover the financing gap, standing at US $8 billion as of end of June 2019.

In this context, the biggest advantage of going to the IMF is that large external funding resources become available at concessional rates. According to the IMF, the total resources that have become available to Pakistan as a result of the three year EFF will be US $38 billion. This will help cover the external financing shortfall and help to rebuild the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

The government has also hinted a return to the international bond markets with a new issuance. This will be Pakistan’s first issuance in the market since November 2017. In that auction Pakistan raised US $1.5 billion through a 10-year Eurobond, and another US $1 billion was raised through a 5-year Sukuk. At that time, the market participation was overwhelming and bids worth US $8 billion were raised. Today, the credit default swap (CDS), the cost of insuring against default by Pakistan, has come down to 370bps, down from 450bps in March 2019. Risks are likely to reduce further with news of the IMF programme kicking off. A rating upgrade may be in store by end of the year too. Hence, this is an excellent time for Pakistan to tap the international bond markets.

After avoiding a hard landing, how to take off?

Now that the country has avoided a hard landing, the government needs to start exploring new drivers of growth and productivity gains to jumpstart the economy. There are three areas that can serve as platforms for serious enhancements to GDP growth.

Accelerating Financial Innovation: According to the SBP Digital Financial Services[i] (DFS) April 2019 report, it is estimated that the market potential of digital financial services in Pakistan is over US $36 Billion. Given the appropriate policy shifts and private sector participation, this quantum is achievable prior to 2025. A potentially massive boost to the GDP. McKinsey’s 2016 report on emerging markets shows that the financial industry can create four million new jobs and lead to the creation of new wealth exceeding US $263 billion[ii]. This potential can only be achieved through a robust and efficient DFS ecosystem. There are reasons to be hopeful for Pakistan in this sector. The SBP recently launched a comprehensive set of regulations for setting up Electronic Money Institutions (EMI). SBP should target to auction at least six EMI licenses in a transparent and competitive manner. Financial advisors should be hired to structure the transaction to attract new foreign investment into Pakistan. Year-on-year growth in financial transactions conducted via mobile phones in Pakistan was nearly 200% in FY18. This signifies enormous potential.

Alternative solutions for big infrastructure projects: Presently, an overwhelming number of public infrastructure projects are funded either directly through the budget, or indirectly through the provision of sovereign guarantees. But many of these could be alternatively financed through Public Private Partnership (PPP) arrangements. This would reduce government liabilities and some calculations suggest that PPPs can offer a potential boost of as much as 5% of GDP over the next five years. To tap this potential, government needs to strengthen the institutional, legal, and regulatory frameworks for PPPs through Amendments in a law originally enacted for PPPs in 2017. The framework for the Viability Gap Fund (VGF Rules); Pakistan Development Fund (PDF Rules); along with procurement and conduct of business rules need to be finalized.

Operationalizing CPEC trade corridor: In the medium term, the operationalization of the CPEC trade corridor can provide a potential boost of over 5% of the GDP through higher trade and investment flows. There are risks of a slowdown in spending on CPEC transit infrastructure projects and development of Special Economic Zones (SEZs). Fast tracking the development of SEZs under CPEC would provide an unprecedented opportunity to both expand exports and connect to global value chains. Bureaucratic red-tape, systemic inefficiencies and a lack of inter-ministerial and inter-departmental coordination must not be allowed to get in the way of an early and urgent operationalization of SEZs. A degree of donor fatigue risks being established in the relationship, and worries about a focus on short term financing taking priority over the long term strategic Pakistan-China framework are not unfounded. This is primarily due to the external funding challenge facing the economy over the last twelve months. With the IMF programme now secured, it must be an urgent priority for the government to revitalize this crucial relationship, in part, by fast-tracking the work on CPEC projects and engaging the Chinese authorities on increasing the size of transit trade and business-to-business joint ventures.

If these three areas are prioritized, the stability afforded by the newly approved IMF programme may serve as a launchpad for sustained higher GDP growth. Pakistan has not been able to take advantage of the stability afforded by previous programmes, by eschewing reforms and delaying investments in more robust economic policy making. If the government maintains its commitment to reform, refuses to give into special interests, and opts for innovation and urgency, this time could be different.

References

[i] http://www.sbp.org.pk/psd/2019/C1-Annex-A.pdf

[ii] Mc Kinsey Global Report, “Digital Finance for All: Powering Inclusive Growth in Emerging Economies” Sep 16

A Financial Markets Specialist with over 18 years of experience in banking. He is a visiting faculty member of IBA Pakistan and a non-resident Fellow on Economics and Finance at Tabadlab.