You can download the PDF version here.

Context

On November 28, 2022, the Foreign Office of Pakistan announced that Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Hina Rabbani Khar would visit Kabul. Her delegation included Special Representative of Pakistan to Afghanistan, Ambassador Muhammad Sadiq and officials from the ministries of commerce and finance.[1] The purpose of the visit was to improve bilateral relations, and especially trade – given Pakistan’s stated priority to alleviate the severe economic pressure faced by the people of Afghanistan.[2]

Almost simultaneous to the announcement of the Khar visit to Kabul came the Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan’s (TTP) statement that it was ending the so-called indefinite ceasefire it had claimed to agree to in June 2022.[3] With the formal announcement of what was, in effect, a scaling up of its terrorist activity in Pakistan, the TTP said, “As military operations are ongoing against mujahideen in different areas, … so it is imperative for you to carry out attacks wherever you can in the entire country.”

Four days after the announcement ending the ceasefire, terrorists attacked the Pakistan embassy in Kabul[4] targeting the Pakistani head of mission, Ubaid-ur-Rehman Nizamani. Mr. Nizamani survived the attack, having taken charge of the Pakistan embassy in Kabul only four weeks prior.[5] In addition to strongly condemning the attack, Pakistan’s Foreign Office announced that the Government of Pakistan and the interim Afghan authorities were working closely to determine the veracity of the Islamic State in the Khorasan Province’s (ISKP) claiming of the attack.[6] ISKP has deep linkages with the TTP,[7] predominantly through their co-location in Afghanistan.

Although the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) have condemned the attack, and ISKP has claimed responsibility for it, a terrorist attack on the lead Pakistani diplomat in Afghanistan so soon after the end of the TTP’s so called ceasefire raises serious questions in Islamabad. International outcry and condemnation of the attack has been largely muted, especially given the high rank of the Pakistani diplomat in question and the wider implications of a terrorist attack of this nature. Though not overtly related to these events, the new Chief of Army Staff (COAS), General Asim Munir, issued a statement declaring the military’s willingness to reengage in kinetic operations to protect civilians from the threat of terrorism.[8]

Negotiations and Ceasefires

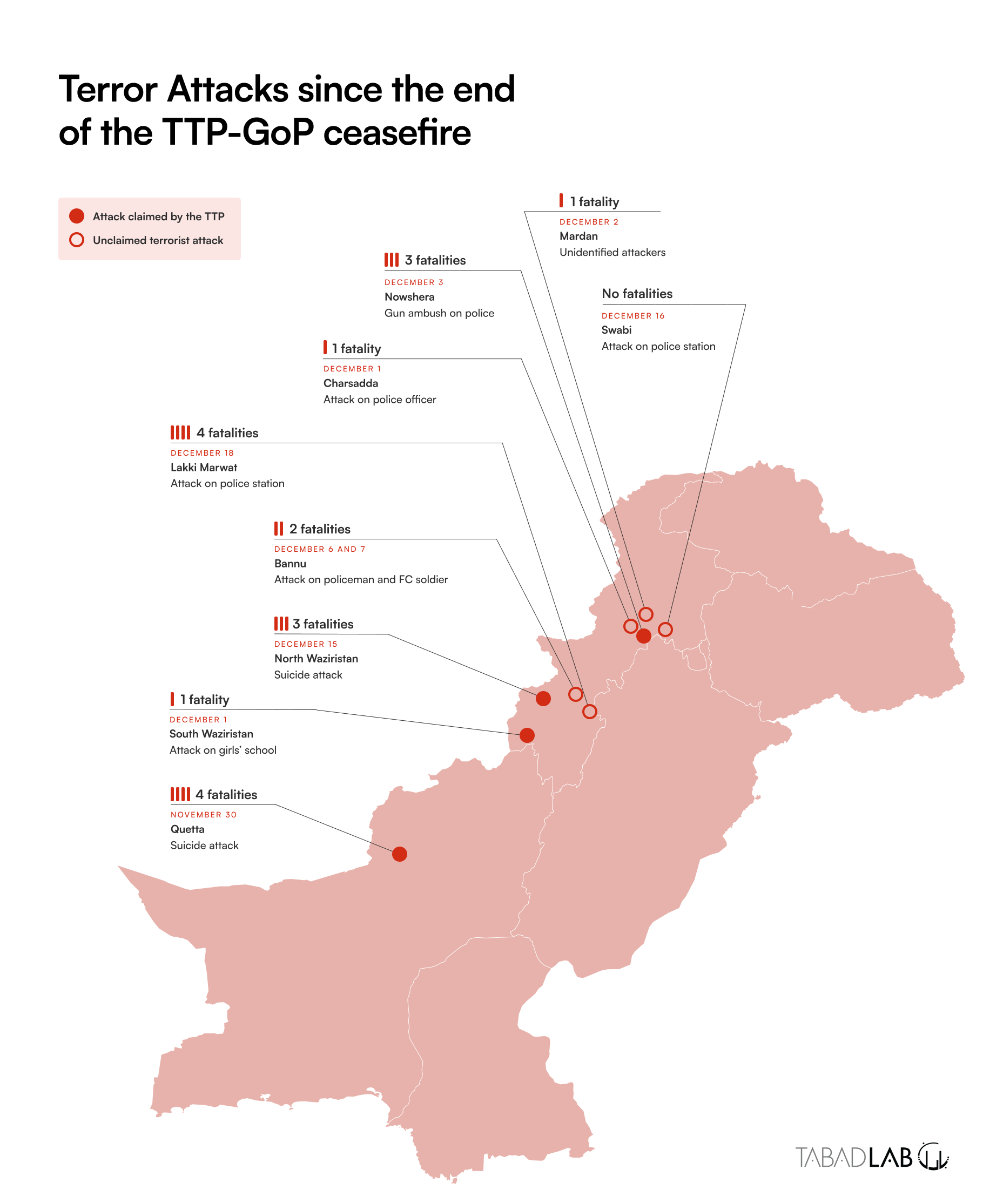

For all intents and purposes, the ceasefire was null and void for months, and the announcement on the 28th of November simply formalised that – but the escalation in violence makes it apparent that the formal end to the ceasefire has enabled TTP to declare open season across the country.

The history of Pakistan’s negotiations with the TTP, ceasefire agreements, and other political concessions is quite clear. The end of the latest so-called ceasefire[9] represents the latest in a long series of attempts[10] by Pakistan to find alternatives[11] to military action against the TTP – efforts that are fifteen years old, tracking all the way back to 2007. Negotiations have nearly always failed, despite the Pakistani state offering a range of concessions, including involving tribal leaders in the conversation, releasing TTP prisoners, and repatriating terrorists’ families. The TTP has consistently used negotiations to normalise anti-state discourse – demanding measures that effectively equate to the dismantling of the Pakistani republic.

Traditionally, ceasefires have been leveraged not as tools of violence-mitigation, but to buy time. For the TTP, it allowed for regrouping, stocktaking, and strengthening. For the Government of Pakistan, ceasefires have been seen as a way to generate respite for frontline forces, and allow for strategy assessment, and redeployments, as well as the application of political pressure. For fifteen years – efforts to negotiate politically with a violent extremist group that employs terrorism as its primary instrument of politics – has only resulted in the weakening of the Pakistani position, and an eventual return to violence. The latest ceasefire episode has been no different.

Past Efforts: Containment and Management

At a cursory glance, one could make the argument that trying to negotiate with a banned, violent, anti-state group indicates that the Pakistani state has not been able to implement its writ upon its sovereign territory. However, the circumstances of this set of negotiations and the short-lived ceasefire are more complicated than that.

First, the TTP and its leadership is no longer in Pakistan. The estimated 5,000 or so fighters of the TTP reside primarily in the bordering provinces of neighbouring Afghanistan.

Second, while Pakistan has the air capability to target TTP hideouts in Afghanistan, it does not have the foot intelligence to mitigate civilian casualties, and any cross-border air strikes would result in further alienating an increasingly distanced Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA).

Third, a ceasefire is also a mechanism to provide temporary relief – both to the active troops on the ground, and the civilian populations that have suffered nearly two decades of violence – particularly in the NMDs and wider Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

How has the TTP survived?

The obvious question is: why, after the concerted and highly successful Zarb e Azb military campaign of 2014, was the TTP allowed to survive and eventually coalesce in 2019 to form the group as it stands today?

First, under tremendous pressure from the concerted kinetic military and intelligence operations, the group splintered into multiple factions and scattered across various geographics, on both sides of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. This made it very difficult to target and eliminate its members, track down its leadership, and shut down its operations entirely.

Second, the Doha pact[12] signed on February 29, 2020, between the Trump administration and the Afghan Taliban (notably without any representation of the Ghani regime) created legitimacy for the Afghan Taliban. This had significant knock-on effects on the Afghan Taliban morale (in terms of their recruitment, and consolidation of assets and power), and emboldened affiliated groups, as well as the TTP. Combined with the drawdown announcement in April 2021,[13] and a reiteration of this promise in July 2021,[14] this further accelerated the Afghan Taliban’s campaign, which was already sweeping across the country and eventually resulted in the takeover of Kabul on August 15, 2021.[15] By extension, the recently re-coalesced TTP[16] also felt empowered, considering its allegiance to the Afghan Taliban.

Third, shortly after the takeover of Kabul, the IEA also released hundreds of TTP fighters[17] from various prisons, including founding deputy emir Maulvi Faqir Muhammad. The TTP was also given complete freedom of movement and operations, and its emir Noor Wali Mehsud renewed its pledge of allegiance[18] to the Afghan Taliban. The TTP had a significant base in Afghanistan that was only bolstered and further legitimised by the prisoner release. While the two have coexisted physically, and operationally intertwined against international forced, the Afghan Taliban have never actively encouraged attacks inside Pakistan.

Fourth, the release of prisoners is a negotiation tactic between the Government of Pakistan and the TTP. In November of last year, the TTP demanded the release of its fighters[19] as a pre-condition for talks. This demand was met by Pakistani authorities, and up to 100 TTP prisoners were released[20] in early December 2021, and again[21] in May 2022. While this is a diminishing resource, given that an emboldened TTP had carried out attacks killing hundreds in Pakistan since August 2021, allowing known enemies of the state to escape the rule of law, is of questionable utility.[22] A related question here is why captured members were not tried, prosecuted, and sentenced at the scale needed to establish the writ of the state, despite a carte blanche being given to the military courts under the NAP.[23]

Fifth, the Pakistani state’s historic insistence on viewing certain groups, especially the Afghan Taliban, as a strategic compulsion, complicates its ability to rationally negotiate with a group allied to them but opposed to the Pakistani people and Pakistani state. Former Prime Minister Imran Khan went so far as to say that the only solution to the TTP problem was a political settlement.[24] Adding to the confusion was the claim by President Arif Alvi and the former PM that an amnesty was on offer if the group laid down its arms. A military spokesperson also confirmed[25] that the recent (now failed) talks and ceasefire was requested by the IEA, emphasising Pakistan’s blind spot when it comes to the Afghan Taliban leadership.

Who will be the likely targets?

While the end of the ceasefire has been declared as a consolidated effort against the state of Pakistan, in practical terms, this means an increase in attacks and violence in the NMDs, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (particularly Swat, Upper Dir, and Lower Dir), and the Quetta Block (comprising of districts Quetta, Pishin, Killa Abdullah).

Given historical precedents and the souring of public opinion against the TTP, particularly after the APS attack, it is unlikely that they will purposely target civilian populations and installations. The bulk of the terror attacks will likely be conducted against security forces in the border and adjoining areas, particularly less-defended security check posts, border outposts, and patrolling convoys. It also follows that a greater volume of attacks will result in an escalation in counter-terrorism operations as well.

What are some factors influencing the situation?

Patronage from the Afghan Taliban: Members of the TTP – estimated to be around 5,000 within Afghanistan, with patronage, support, and freedom of movement for their members – reside in provinces bordering Pakistan, particularly Kunar, Khost, and Paktika. They are well-organised, equipped, trained, and mobile. This patronage from the Afghan Taliban regime, in direct violation of the Doha agreement, will likely continue. Having deep roots in Al Qaeda and connections with the Islamic State in the Khorasan Province (ISKP), the IEA would be keen to keep the significant TTP presence appeased and in check, rather than having them turn on them, or worse, join the ideologically opposed ISKP. While negotiations between Pakistan and the TTP occurred at the facilitation and behest of the IEA, with no resolution and the lifting of the ceasefire, the IEA is now in a very precarious and unenviable position.

The Pakistan-Afghanistan relationship: Another factor is the ability for Pakistan to leverage its relationship with the IEA, and the impact that may have on the internal dynamics of Afghanistan. A day prior to the announcement of the end of the ceasefire, the Pakistan Foreign Office announced that Minister for State Hina Rabbani Khar would be visiting Kabul.[26] This inevitably also changed the ensuing dialogue to be more security-focused, with emphasis placed on curbing cross-border attacks on Pakistani security forces, as well as mitigating the movement of armed fighters across the fenced position. Following the attack on Pakistan’s head of mission in Kabul, the Foreign Office issued a statement demanding that “the interim government of Afghanistan must immediately hold thorough investigations in this attack”[27] and hold culprits to account. In response, the IEA has also issued a statement condemning the attack and assuring a “serious investigation,”[28] but the tangible consequences remain to be seen. Over time, Pakistan’s relationship with the Islamic Emirate, both in terms of its perceived leverage over the group, and the Emirate’s willingness to accommodate Pakistani demands, has been increasingly grounded against its own internal risk matrix.

Border dispute: The border between Pakistan and Afghanistan continues to be a thorny issue and has been politicised to suggest that Pakhtuns on both sides believe it to be a barrier to their long-standing ties and mobility. This may be true for the Afghan side, but it is not necessarily the case on the Pakistani side. It is also a contentious issue for the Afghan authorities, given the several[29] border[30] skirmishes[31] that have broken out[32] along[33] the fenced position, often resulting in closing of border crossings.[34]

TTP’s operational capacity: Assessing the access and capability of the TTP – both the released fighters within Pakistan, and the bulk of its operational forces in Afghanistan – is a key consideration. Pakistan’s security apparatus needs to do better in terms of building local trust and buy-in, as well as establishing stronger foot intelligence to aid in early warning and prevention.

Pakistan’s economic and political crisis: Pakistan is also facing a range of internal political and economic crises. The country is going into an election season with political rivalries and acrimony at an all-time high, thereby affecting political priorities and focus. In addition, after six years, the Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) was appointed[35] a few days prior to the annulment of the ceasefire. This has implications both in the context of the prioritisation of national security in the face of the TTP threat, and how the military establishment works with the civilian government to tackle the long-standing TTP puzzle.

Centre-province divergences: The federal-provincial divide in Pakistan has historically resulted in political point scoring and blame gaming, instead of broad collaboration to tackle the many challenges, particular in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the tribal regions. Over the course of time, PTI’s strong popularity in the region and the party’s alienation from the military after the change in government in Pakistan in April 2022 has resulted in significant challenges for the alignment between the security sector and the wider public and political discourse.

Seasonal capability: One factor that limits the TTP’s ability to strike targets is the onset of the winter season. There is sufficient historical evidence to suggest that the ferocity and frequency of attacks lessens in the winters. However, given that the end of the ceasefire was announced at the end of November, the TTP has also conducted attacks to establish legitimacy, tactical prowess, and strike capability.

What does Pakistan need to do?

The TTP in December 2022 represents an urgent national security challenge for Pakistan. Small groups or “tashkeels” have been infiltrating through Dir for years. This time, ostensibly buoyed by the Pakistan-TTP talks, these armed members have stayed – leading to local populations pushing back through several protests in the region.[36] Any TTP terrorists on Pakistani soil pose a clear and present danger to society, the state and the security sector in the region. In the absence of effective elimination, apprehension, or movement restriction, these terrorist “fighters” (more than one hundred of whom were recently released[37]) are an immediate problem. The fighters residing in Afghanistan constitute the next priority or group of concern.

Pakistan’s TTP problem has been decades in the making, and has now lasted for fifteen years. It is clear, both through historical precedent and the obduracy of the TTP, that a political settlement or permanent ceasefire are not an option. Given the violent attacks over the last fifteen months, despite the so-called ceasefire, the group has signalled its intent to inflict damage and continue to undermine to undermine the Pakistani republic, particularly in the newly merged tribal districts regions bordering Afghanistan.

Containment, management, and the eventual cycle of negotiations and ceasefires needs to be catalogued as ineffective and shelved as a serious option for Pakistan. The country has suffered tremendously at the hands of terrorist groups in the last two decades, and all prior attempts at reconciliation, political settlement, or ceasefire have failed, save the temporary reduction in hostilities that these agreements offer.

A major shift in thinking is overdue, one that is mandated by both the 25th Constitutional Amendment and the very pronounced public outcry against the TTP resurgence over the last three years. Pakistan’s political and security sector need to better respond to the needs and demands of right-based movements like the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement, and forge better political buy-in from local communities that are most deeply affected by the TTP’s violence. Policies, postures and politics that causes the alienation and disenfranchisement at the grassroots is a formula for an ever growing TTP footprint and expanding distance between Islamabad and the people. The strong public sentiment against the group needs to be channelled and responded to by the state, rather than undermined or propagated against.

What Pakistan must do internally:

- Identify, stop, and prosecute terrorists by mandating and empowering civilian law enforcement, administration, judicial bodies. This needs to be the de facto state policy with two caveats:

- First, any prisoners of this conflict must be treated following the stipulations of the Geneva Convention[38]

- Second, effects on the local population must be accounted for, and efforts made to shield them from displacement or disruption in livelihoods

- Third, there is no tactical reason for not offering amnesty to terrorists that lay down their arms, but it must be accompanied with the application of the rule of law to said individuals. This can be an easy step toward splintering group cohesion and obtaining updated intelligence from surrendering terrorists.

- Vigilantly monitor, patrol, and control the now-fenced border, with clear rules of engagement established with border control authorities and governments on both sides. Border posts are likely to remain easy and primary targets for inflicting damage, and non-crossing sections for attempting infiltration. Pakistan has been fencing the border for nearly six years, with 94% of the work complete by January 2022,[39] and has maintained for a long time that the border is a settled issue.[40] However fencing must be 100% complete for this to be an effective tool.

- Heighten security in sensitive installations across the country, but particularly in the newly merged districts and other adjoining areas

- Enhance, develop and renew foot intelligence or human intelligence networks, building confidence with the local This is necessary both to thwart the potential recruitment of marginalised communities (particularly youth) by the TTP, and to provide actionable information and intelligence to pre-empt potential terrorist planning and attacks.

- Cross-border military operations, such as the airstrikes conducted earlier this year are the least desirable option. The previous airstrikes, which reportedly killed at least 47 civilians in Afghanistan April 2022,[41] had limited tactical applicability and negligible strategic value. If anything, it weakened Pakistan’s position in the negotiations with the TTP facilitated by the Afghan Taliban government. Airstrikes also draw the ire of the Afghan Taliban and the international community, particularly since the April strikes came under severe criticism by both the UN and the public in Afghanistan.[42]

- The release of TTP prisoners as a tool for negotiation and a confidence building measure is a diminishing resource with limited efficacy. Pakistan needs to properly prosecute TTP prisoners and use the resulting justice as a deterrent and a signal of the state’s strong intent and will to pursue and punish terrorists.

What Pakistan must do regionally:

Diplomatic

- Apply pressure on the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IAE) to keep the TTP in check and restrict its movement across the border. This is problematic because a) the TTP has sworn allegiance to the Afghan Taliban, and b) their raison d’etre is to conduct terror operations against the Pakistani state and security forces, supporting the IEA, and the eventual imposition of their version of Shariah law in Pakistan.

- Think beyond the carrot and stick approach of pushing for the repatriation of Afghan refugees, tightening of the visa regime, and border closures as effective policy instruments to coerce the IEA. These interventions only result in further alienation and resentment of ordinary Afghans.

- Continue to build regional consensus and pressure, particularly from Afghanistan’s neighbours and the GCC to ensure that the IEA does not support, patronise, or shelter violent groups that are a direct threat to countries like Pakistan, China, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Iran. In this context, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are of particular significance, as the IEA survival is increasingly tied to the Afghan Taliban’s legitimacy.

Military

- Consider engaging with international partners (including both bilateral and multilateral partners) to explore deeper joint intelligence work, as well as options for joint over-the-horizon kinetic operations and strikes that target key terrorist leaders and networks – instead of relying on unilateral operations. Bilateral partners may include the United States, whilst multilateral partners may include a range of potential regional frameworks, including the SCO, GCC and others.

- Forge better intelligence gathering and sharing with key partners, including Afghanistan’s neighbours and the US to better facilitate tracking, targeting, and elimination of key terror figures.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Tabadlab Private Limited.

Endnotes

[1]https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/1014556-hina-rabbani-to-visit-afghanistan-on-29th

[2]https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2021/03/24/pakistan-loses-spot-as-top-trade-partner-of-afghanistan/

[3]https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/3/pakistan-taliban-says-ceasefire-with-govt-in-islamabad-extended

[4] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/12/2/assassination-attempt-on-pakistan-envoy-in-afghan-capital

[5] https://www.pakembassykabul.org/en/information/ambassador/

[6] https://mofa.gov.pk/press-release-546/

[7] https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/12/21/evolution-and-future-of-tehrik-e-taliban-pakistan-pub-86051

[8] https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/pakistans-new-army-chief-says-will-defend-motherland-during-visit-disputed-2022-12-03/

[9]https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2022/11/taliban-ends-ceasefire-with-pakistani-government-vows-revenge-attacks-across-the-country.php

[10] https://www.dawn.com/news/1660188

[11] https://www.dawn.com/news/1660188

[12] https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/02.29.20-US-Afghanistan-Joint-Declaration.pdf

[13]https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2573268/biden-announces-full-us-troop-withdrawal-from-afghanistan-by-sept-11/

[14]https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/07/08/remarks-by-president-biden-on-the-drawdown-of-u-s-forces-in-afghanistan/

[15] https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/taliban-afghanistan

[16] https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/tehrik-i-taliban-pakistan

[17]https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/12/21/evolution-and-future-of-tehrik-e-taliban-pakistan-pub-86051

[18] https://twitter.com/IftikharFirdous/status/1427543775178600477?s=20

[19]https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/pakistan-taliban-demand-prisoner-release-condition-talks-sources-2021-11-06/

[20] https://tribune.com.pk/story/2333199/dozens-of-ttp-members-freed-as-truce-holds

[21] https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/pakistans-peace-gamble-with-the-tehreek-e-taliban-pakistan/

[22] https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/01/after-talibans-takeover-pakistans-ttp-problem

[23] It is worth mentioning here that under the NAP-mandated military courts, 345 people were sentenced to death, and of the 8,000 or so prisoners on death row, another 56 were hanged. The latter also required the reversal of a moratorium that has been in effect since 2008, and is back in effect now, at least in spirit, if not in letter. The last sentencing was in 2019, and the last hanging was in Dec 2019.

[24] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/02/world/asia/pakistan-taliban-talks.html

[25]https://www.newsweekpakistan.com/military-ops-against-ttp-to-continue-till-menace-wiped-out-dg-ispr/

[26] https://dailytimes.com.pk/1033490/hina-rabbani-khar-in-afghanistan-on-day-long-visit/

[27] https://www.dawn.com/news/1724302

[28] https://dunyanews.tv/en/Pakistan/677949-Afghan-govt-condemns-attack-on-Pakistan-envoy;-assures-/’serious-investig

[29] https://arynews.tv/pakistan-army-soldier-martyred-cross-border-attack-ispr/

[30]https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/29/pakistani-soldiers-killed-in-cross-border-fire-from-afghanistan

[31] https://www.dawn.com/news/1665630/border-spat-with-taliban-resolved-official

[32]https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/five-pakistan-soldiers-killed-attack-afghanistan-military-says-2022-02-06/

[33]https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taliban-pakistani-forces-clash-along-border-casualties-reported-2022-09-14/

[34] https://tribune.com.pk/story/2386288/chaman-border-closed-for-indefinite-period-following-clashes

[35] https://tribune.com.pk/story/2388664/new-coas-gen-asim-takes-reins

[36]https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/10/11/thousands-protest-rising-violence-in-pakistans-swat-valley

[37] https://tribune.com.pk/story/2330584/govt-releases-over-100-ttp-prisoners-as-goodwill-gesture

[38] The status of the enemy, under international law, is quite complicated. In one instance, this is non-international armed conflict; on the other TTP’s majority in Afghanistan implies it is international armed conflict.

[39] https://tolonews.com/afghanistan-176201

[40] https://www.dawn.com/news/759523/durand-line-a-settled-issue-says-pakistan

[41]https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220417-afghanistan-death-toll-in-pakistan-strikes-rises-to-at-least-47-officials

[42]https://www.voanews.com/a/taliban-condemn-pakistan-for-alleged-cross-border-attacks-in-afghanistan/6532351.html

Zeeshan Salahuddin

Zeeshan Salahuddin is the Director for the Centre for Regional and Global Connectivity (CRGC) at Tabadlab. Zeeshan’s research focuses on security studies, particularly religious and political extremism in Pakistan, and its priorities in an increasingly multipolar world. He frequently writes for The News, The Friday Times, Dawn, The Diplomat, Foreign Policy, and others, and occasionally provides analysis on BBC and CNN. He has a master’s degree in Corporate Communications and Strategic Management from Ithaca College, New York.