You can download the PDF version here.

The Problem: A Nationwide Shortage of Panadol

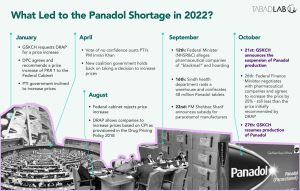

On October 21, 2022, in a regulatory filing to the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX), GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare (GSKCH) Pakistan Limited formally announced the suspension of manufacturing Panadol – a generic paracetamol drug for reducing pain and fever.[1]

The news came after months of reported shortages of the product in the market, and GSKCH’s persistent requests to the regulatory authorities to increase the selling price of the drug owing to the marked increase in costs of input materials. GSKCH has now restarted manufacturing Panadol, but this was not the first time that a pharmaceutical product was unavailable in the market due to price controls and other regulatory challenges. To understand the factors that led to the shortage, it is critical to understand the series of events that preceded it.

Events Leading Up to Suspension of Panadol Production

Amid increasing prices and the depreciating value of the Pakistani Rupee (PKR), in January 2022 GSKCH requested – and received – an approval to increase the price of Panadol from the Drug Pricing Committee (DPC) of the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP). The DPC forwarded the recommendation to the federal cabinet, which, after a prolonged delay, rejected the recommendation without intimating any reasons to the company.[2]

On August 25, 2022, DRAP did grant GSKCH a routine Consumer Price Inflation (CPI) adjustment for 2022 – as the drug pricing policy allows pharmaceutical companies to increase the prices of their products according to inflation measured by CPI. However, this was not sufficient to counter the exorbitant increase in raw material costs.[3]

The Recent Panadol Saga

Earlier this year, the PTI government had agreed to increase drug prices. However, before an official decision could be made, then Prime Minister Imran Khan was ousted by a ‘vote of no confidence’.[4] Under pressure, the new coalition government “got cold feet”[5] and did not follow through on the previous government’s decision. GSKCH, which manufactures 450 million Panadol tablets a month,[6] reduced its production by one-third, starting the shortage in the market.[7]

Although Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif did step in later (September 2022) to announce subsidies to producers of Paracetamol,[8] removing duties and taxes on Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) required to produce the drug.[9] However, it could not materialise due to limited fiscal space and no rules to implement the subsidy,[10] while pressures on pharmaceutical companies continued to mount.

As described above, since DRAP recommended a price increase of PKR 1 for all paracetamol tablets[11] and the federal cabinet subsequently rejected the summary, the situation evolved in an unprecedented fashion. On September 12, 2022, the Federal Minister for National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination (NHSR&C) Abdul Qadir Patel commented that the medicine remains in abundance and the government will not increase prices, while alleging pharmaceutical companies of “blackmail” and creating an artificial shortage.[12]

On September 16, 2022, Sindh’s health authorities raided the warehouse of a distribution company named Connect – a subsidiary of GSKCH. They found 48 million Panadol tablets at the warehouse and accused GSKCH of hoarding the paracetamol medicine.[13] The confiscated inventory was estimated to be worth PKR 250 million.[14]

GSKCH responded by clarifying that this stock was scheduled to be ‘released and distributed in the country in the normal course of business.’[15] As per the company’s Supply Chain Policy, it is a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) to maintain a 30-day safety stock at their warehouse.[16]

Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry does not produce most of the active ingredients required to manufacture drugs, making the industry dependent on the import of raw materials to continue production.[17] Furthermore, these imported ingredients have themselves been difficult to procure in the international market due to global supply shortages and disruptions, as well as the depreciation of the PKR.[18] In case of producing Panadol tablets, GSKCH purchases a “major chunk” of paracetamol from Citi Pharma Limited, whereas the raw material used by Citi Pharma to produce paracetamol is imported, making it subject to the challenges described.[19]

The matter was finally resolved when Federal Finance Minister Senator Mohammad Ishaq Dar met with the heads of Pakistan’s major pharmaceutical companies on October 26, 2022.[20] GSKCH has restarted production of Panadol as all parties negotiated to a middle ground by increasing the price of a 500mg tablet of paracetamol to PKR 2.35, an increase which is 50% less than the initial proposal.[21]

The Wider Repercussions: Another Dent to Investor Confidence

The unfair treatment GSKCH has faced at the hands of the public authorities during the Panadol shortage has further hurt foreign investor confidence, as many multinationals have already pulled out of the country in the recent past due to government’s ad hoc policies and regulations[22] – over the last 18 years, 26 international pharmaceutical companies have stopped operating in Pakistan.[23]

Recently – in November 2022 – Eli Lilly Pakistan (Pvt) Limited also announced that it is ceasing operations in Pakistan, while sources from Pakistan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (PPMA) commented that three more multinational pharmaceutical companies are planning to leave Pakistan in 2023.[24]

The Panadol fiasco has also damaged the sentiments of the local business community, as they perceive these events as yet another series of avoidable losses for the industry,[25] incurred only due to a fractured regulatory system.

Populist Policies at Play: Decisions to increase or decrease pharmaceutical product prices are always shaped by populist political narratives rather than sound industry expertise and market requirements. Federal Minister Abdul Qadir Patel’s remarks of being ‘blackmailed’ and asking media outlets to investigate or expose pharmaceutical companies can also be considered an example of this. Similarly, it is interesting to note that there have been multiple recent instances where the government/federal cabinet has rejected the price increase recommended by DRAP.[26] [27] [28]

The Context: Pharmaceutical Sector Regulation and Price Controls

The pharmaceutical industry of Pakistan is subject to substantial government control. From licensing to manufacturing, importing and/or distributing to advertising, pricing, and public procurement almost all aspects of the industry are regulated. While many of these regulatory features may be debatable, this paper will focus on one of the most contested topics, pricing.

Over the course of time, pricing regulations have been, evolved, dictated, and governed by three main legal actions:

- Drugs Act 1976

- DRAP Act 2012

- Drug Pricing Policy 2018

Drugs Act 1976

The Drugs Act of 1976 was introduced during Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s regime in a bid to prevent the consumption of ‘dangerous or substandard’ medicines and keep medicines affordable for the public.[29] The 1976 Act gives the Federal Government power to ‘fix [the] maximum prices of drugs’ at which they are to be sold, and ‘specify a certain percentage of the profits of manufacturers of drugs’ for research on drugs.[30] It still remains the primary legislation that governs the pharmaceutical industry.

While this was a well-intended initiative, the Drugs Act of 1976 did not establish any formula on how the government will determine prices. Consequently, during the policy period, the Maximum Retail Price (MRP) of drugs were fixed on an ad hoc basis.[31] Under the same policy, Pakistan’s pharmaceutical industry also saw ‘a virtual price freeze on medicines’ from 2001 to 2013[32] – a period where private companies struggled to continue business operations as margins diminished due to rising costs.

DRAP Act 2012

In the backdrop of 2010’s 18th Amendment (which devolved the management of public health to the provinces), a virtual price freeze, and mounting pressures on public stakeholders to efficiently regulate the industry, the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP) Act 2012 was legislated. The DRAP Act 2012 allowed the establishment of DRAP, an autonomous arm of the Ministry of National Health Services Coordination and Regulation (MNHSCR). DRAP replaced the Drug Control Organisation (DCO) which worked prior to devolution.[33] After devolution, and the introduction of the 2012 Act, provinces controlled the distribution and sales of drugs, but the federal government managed all other aspects (licensing, pricing, import, export, manufacturing, etc.).[34]

DRAP carries out its administrative role through three boards[35]:

- Policy Board – responsible for overall management and executive decisions of DRAP

- Licensing Board – grants licenses for the manufacture of therapeutic goods

- Registration Board – regulates the grant of registration to therapeutic goods

The regulatory body provides strategic support to the provincial health departments and works in tandem with the respective Provincial Quality Control Boards.[36]

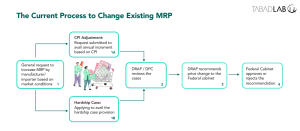

Drug Pricing Committee (DPC)

The rollout of DRAP Act 2012 provided the impetus to formally constitute a Drug Pricing Committee (DPC) through a Statutory Regulatory Order (SRO) on August 6, 2013.[37] The DPC was vested with the responsibility to formulate the pricing of drugs throughout the country.

Later, court orders clarified that DPC would only recommend prices, and the final decision regarding price changes will be taken by the Federal Cabinet.[38]

The members of the committee comprise of[39]:

- Director Costing and Pricing, DRAP

- Secretaries, Department of Health from each province or their nominees not below the rank of an officer of BPS-19

- Chief Cost Accounts Officer or Cost Accountant, Ministry of Finance, Government of Pakistan

- Deputy Director General (Pricing)/Deputy Drugs Controller (Pricing), DRAP

- Representative of Pakistan Medical Association

- Representative of Consumer Rights Commission of Pakistan

- Representative of Pharma Bureau (Overseas Investors Chamber of Commerce and Industry)

- Representative of Pakistan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association

The composition of the DPC was formulated with a view to ensure a wide spectrum of stakeholder representation – from public entities to consumers and commercial businesses.

Drug Pricing Policy 2018

The Drug Pricing Policy – initially formulated in 2015 – was later revised and updated in 2018. Notably, the Drug Pricing Policy of 2018 divides medicines into two categories: drugs and biologicals on the National Essential Medicines List, and all other drugs. The National Essential Medicines List is a list of essential drugs and biologicals published by DRAP, updated or revised after three years in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) list of essential medicines.[40]

The policy primarily follows the External Reference Pricing (EPR) system. DRAP establishes Maximum Retail Price (MRP) for all kinds of drugs. Broadly, if a drug is introduced in Pakistan that already exists in India and Bangladesh, then MRP is set by calculating the average price in the two countries. However, in cases where the drugs are not marketed in these two countries, the MRP is calculated by taking the average retail price of a basket of countries which includes Indonesia, Philippines, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia. The MRP of generics are set at 30% less than the MRP of the Originator Brand (a branded drug containing a new chemical entity developed through research and development).[41]

The policy also allows manufacturers and importers to increase drug prices within a particular set of caveats. In the case of essential drugs or biologicals – excluding lower priced ones – firms are allowed to raise prices by up to 70% of the increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), provided the rise does not exceed 7% of the original amount. Whereas, in the case of all other drugs, biologicals, and lower priced drugs, firms are allowed to raise prices equivalent to the increase in the CPI, so long as that is not greater than 10% of the drug’s original price. However, these increases can only be implemented after authorisation by DRAP.[42]

In the Case of Panadol Shortage:

Paracetamol manufacturers had demanded a price increase of 42.78% (from PKR 1.87 to PKR 2.67) – much higher than the thresholds of 7% and 10% described above. In the end, the government decided to increase the price by 25.67% to PKR 2.35.[43]

The policy also has a provision of ‘Hardship Cases’ where manufacturers and importers under extraordinary circumstances can request DRAP to re-evaluate prices if they are unable to recover costs and profit margins through existing MRPs, with escalating production costs and tightening exchange rates. Companies can apply for this provision once in three years after making an MRP review fee payment.[44]

In the Case of GlaxoSmithKline Pakistan Limited:

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Pakistan Limited has had a rocky relationship with regulators when it comes to applying and availing the ‘hardship case’ provision. The rollout of the first Drug Pricing Policy 2015 mandated that all hardship cases will be decided within nine months. However, GSK Pakistan’s prior applications to avail the provision did not receive any decision in the stipulated time. A prolonged delay and multiple court rulings (both by Sindh High Court and Supreme Court) later, GSK Pakistan was asked to resubmit the applications to DRAP – a tedious process, with looming uncertainties of adverse financial impact.[45]

From Skewed Incentives to Force Majeure: Stakes and Incentives

To understand the nature of this regulatory challenge, it is crucial to first identify the stakes and incentives for the three key actors in this space.

Pakistani Consumers

The two critical considerations for consumers of pharmaceutical products are affordability and accessibility. In 2019, the out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure in Pakistan as a percentage of total health expenditure was 53.81%.[46] Moreover, the 2019-20 National Health Accounts survey showed that 50.63% of the total OOP Expenditure on health by private households was on “medicines/vaccines”.[47] Therefore, in the current scenario, drug prices are a major concern for the ordinary consumer, explaining the persistent public opposition to exorbitant hikes in drug prices.

Another increasingly significant demand of consumers is accessibility to all kinds of pharmaceutical products. Even after the introduction of DRAP, shortage of medicines remains a common phenomenon. The reasons for scarcity in supply range from contested prices to inefficient procurement processes at the provincial health department levels. The growing frustration of the public is justified: over the past decade, common medicines like Panadol, Buscopan, Ritalin, and Sovaldi have all seen shortages in the Pakistani market and have been sold in the black market for higher prices.[48]

Pharmaceutical Manufacturers, Importers, and Distributors (Local and Multinationals)

The private sector sees the current regulatory structure as too tight, with limited room for innovation and expansion. While private entities wish to increase their margins and maximise their profits, they are also a driver of research and innovation. Multi-National Corporations (MNCs) provide healthy competition to local players and influence them to continue evolving their products and processes. The private sector requires a regulatory structure that will enhance their current supply chains and product offerings rather than restricting or limiting them. While manufacturers, importers and distributors want fewer price controls so that they may increase prices as per market conditions, they are willing to be taxed. These taxes could be used to create funds for research and development, or to provide subsidies to minimise OOP expenditure for the poor.

The Pakistani Government

Government entities – both federal and provincial – and public authorities such as DRAP are all essentially striving to create an equilibrium where

- pharmaceutical products are affordable and accessible for the public;

- the pharmaceutical industry is regulated such that safe products are produced, ethically marketed, and efficiently distributed;

- a business environment is developed which is conducive to the growth of local players within the sector, avoids monopolies and rent seeking behaviour, attracts Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), promotes trade (mostly exports), and helps the industry mature overall; and,

- a fair taxation regime can build funds for research and development is instituted.

Balancing these competing priorities is a tremendous challenge. Without reprioritisation, future goal setting for the industry, and redefining clear roadmaps for entities such as DRAP, this constant push and pull will continue.

While this paper primarily discusses the recent Panadol shortage, drug shortages are not new or limited to any specific medicine. The next section will analyse the larger challenges of the regulatory structure governing the pharmaceutical industry in Pakistan and seek to explain how the current environment has evolved.

The broader challenges

The multiple regulatory issues of the pharmaceutical industry can be classified into four broad categories of challenges as described below.

Inconsistencies in policy directives

Two overlapping but separate sources of inconsistency in policies inhibit private sector confidence and reliability of public stakeholders in the industry:

- Ad hoc-ism due to changing government priorities and lack of mid- to long-term planning – This was evident when, in 2020, holders of valid Drug Manufacturing Licenses (DML) were allowed to manufacture hand sanitisers for three months, but later the directive was reversed by the Cabinet without any formal reason. Similarly, while SROs in 2010 and 2013 discouraged imports, an SRO in 2016 allowed a five-year exemption for the import of drugs meant for donations without any fool proof mechanism to check the abuse of this exemption by individuals or companies.[49]

- Decisions colluded by populism – as mentioned in section 1.2. there have been multiple occasions where recommendations by DRAP’s DPC are rejected by the Federal Cabinet, or the Federal Cabinet has reversed its decision to increase prices due to public outcry. These reversals are charged by political motivations to win over the public and not grounded in the technical expertise required to keep the market afloat. Another example of this occurred in 2013 when the Prime Minister reversed the decision to end the price freeze policy in 2013 within two days of it being taken.[50]

Reactive instead of proactive

On multiple occasions, DRAP’s processes and systems have proven to be slow, and the decision making has been reactive instead of proactive. As can be concluded from this year’s Panadol shortage, DRAP did not have a mechanism to proactively foresee the rising raw material costs for manufacturers and pre-empt the repercussions of the fractured global supply chain caused by the pandemic.

Similarly, during the 2022 floods, multiple drug and medicines shortages were reported across the country.[51] [52] The climate induced calamity created a shortage in both public and private facilities, as the provincial health departments struggled to procure more medicines.[53] [54] The regulator was not able to intervene and ensure a strong – or indeed any – response to mitigate hoarding.

Covid-19 exhibited that DRAP was not prepared to deal with a pandemic. The vaccine procurement process was mostly managed by the Federal Government with limited visibility by DRAP. The regulator had not conducted any research on vaccines and there was no technical or operational expertise to start developing vaccines locally, again leaving the country susceptible to import markets.[55]

Rent seeking

The untimely or delayed increase in prices of drugs also encourages rent seeking behaviour in some ways. When prices are not increased and manufacturing of a certain drug halts, the shortage may benefit some stakeholders of the ecosystem as described below:[56]

- The shortage may be balanced through imports, which will favour importers of similar drugs.

- If the drugs that become too expensive to produce are first-generation drugs, then the same company can start manufacturing and introduce second- or third-generation drugs over the medium-term in the market.

- In instances of shortage, many drugs are hoarded, smuggled, and sold on the black market, thereby creating markets of exploitation.

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) not being produced locally

The amount of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) produced in Pakistan is negligible as 95% of APIs are imported, with India and China being the primary sources.[57] Relying on imports for the raw material for most pharmaceutical products means that Pakistan’s pharmaceutical sector and stakeholders are always susceptible to the impacts of a depreciating local currency, the risk of supply chain breaks, and other externalities.

Recommendations

The pharmaceutical industry must be regulated to keep private stakeholders aligned with the objectives of the government and ensure greater public good by keeping essential drugs affordable and accessible. However, regulatory structure should encourage research, innovation and industry development – especially from local businesses – to make the sector competent, competitive, and future-ready.

DRAP was created to catalyse industry growth, while rationalising commercial incentives and curbing rent-seeking behaviour. The following recommendations may assist in making the regulatory regime and pricing mechanisms more robust and effective.

- Explore and Develop Holistic Pricing Models:

- Shift away from the one pricing model (External Reference Pricing) and introduce a blend of pricing models tailored to Pakistan’s health system and dynamic industry scenarios, that can adjust to the need of the hour.

- WHO describes various pricing models that can be explored by Pakistan, and implemented according to the country’s health system[58] – some suitable models are Internal Reference Pricing, External Reference Pricing (already implemented), Value Based Pricing, Mark-up Regulations.

- Benchmark against countries with similar socioeconomic and industry maturity as Pakistan – not countries like Malaysia who have ‘a free market economy with no control over drug prices.’[59]

- Improve Price Revision Processes:

- Devolve the price change (increase or decrease) responsibility to the DPC or provincial health departments to mitigate political bias and populist decision making.

- Revise and enhance the drug pricing policy to set predefined formulae that automate drug pricing mechanisms for most essential drugs, only requiring final approval from the DPC.

- Stimulate Research and Innovation:

- Effectively utilise the already established Central Research Fund (CRF), a deposit pooled in through contributions amounting to 1% of the gross profits of licensed companies.

- Realign the CRF to effectively utilise the money towards funding research and innovation in the health systems and pharmaceutical industry.

Establish a separate fund – with contributions from private companies – to subsidise OOP healthcare payments for the lowest quintile income groups, instead of tightening price controls.

6. Endnotes

[1] Alam, K. (2022). GSK suspends manufacturing of Panadol, says it’s losing money. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1716270.

[2] Alam, K. (2022).

[3] Alam, K. (2022).

[4] BBC News. (2022). Imran Khan ousted as Pakistan’s PM after vote. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-61055210.

[5] Ali khizar [@AliKhizar]. (2022, October 22-a). Previous PTI govt was about to increase prices; but VONC came. The new govt got cold feet. Refused to do the necessary. GSK reduced the production to 1/3rd. The product got short in the market 2/. Twitter. https://twitter.com/AliKhizar/status/1583688499860905984.

[6] Shahid, A. (2022). The mechanics behind the panadol shortage. Profit. https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2022/09/18/the-mechanics-behind-the-panadol-shortage/.

[7] Ali khizar [@AliKhizar]. (2022, October 22-a).

[8] Daily Pakistan. (2022). Pakistan to subsidise Paracetamol, Panadol as price hike causes shortage amid huge demand. Daily Pakistan. https://en.dailypakistan.com.pk/22-Sep-2022/pakistan-to-subsidise-paracetamol-panadol-as-price-hike-causes-shortage-amid-huge-demand.

[9] Bhutta, Z. (2022). Govt mulls making paracetamol duty free. The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2378824/govt-mulls-making-paracetamol-duty-free.

[10] Ali khizar [@AliKhizar]. (2022, October 22-b). Then PM instead of increasing prices announced to give subsidy with no fiscal space n no rules to dole out subsidy. It was never supposed to happen. Seeing all that GSK declared force majeure to produce Panadol range. 4/. Twitter. https://twitter.com/AliKhizar/status/1583688508639653888.

[11] Shahid, A. (2022).

[12] Junaidi, I. (2022-a). Ministry to inspect pharma units ‘hit by shortages’. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1709859.

[13] Ayub, I. (2022). Over 48m Panadol tablets seized in Karachi raid. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1710347.

[14] Ali, I. (2022). 48m ‘hoarded’ Panadol tablets confiscated from warehouse in Karachi’s Hawkesbay: Sindh govt. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1710249.

[15] Shahid, A. (2022).

[16] Shahid, A. (2022).

[17] Dawn. (2022-a). Panadol shortage. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1711680.

[18] Dawn. (2022-a).

[19] Alam, K. (2022).

[20] Ministry of Finance [@FinMinistryPak]. (2022, October 26). Federal Finance Minister Senator Mohammad Ishaq Dar in a meeting with heads of main pharmaceutical companies discussed the retail price of paracetamol products. The pharma industry agreed upon the reduced prices of paracetamol 500mg tablet at Rs. 2.35,..(1/2)… Twitter. https://twitter.com/FinMinistryPak/status/1585224572571250688.

[21] Business Recorder. (2022). Pharma firms to resume production of paracetamol after meeting with Dar: Ministry of Finance. Business Recorder. https://www.brecorder.com/news/40205268.

[22] Ali khizar [@AliKhizar]. (2022, October 22-c). Outcome – 1. Shortage of most selling product in days of viral spread. Masses to suffer 2. Investors sentiments to dampen as a foreign entity is harrased by one govt n refused for its right by the other. 5/5. Twitter. https://twitter.com/AliKhizar/status/1583688512712232966.

[23] Hussain, B. (2022). Eli Lilly ceases operations in Pakistan. Business Recorder. https://www.brecorder.com/news/40208321.

[24] Bhatti, M.W. (2022). Are pharma MNCs leaving Pakistan? The News. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/1009046-are-pharma-mncs-leaving-pakistan.

[25] The Express Tribune. (2022-a). Panadol shortages cause anxiety in businesspeople. The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2383315/panadol-shortages-cause-anxiety-in-businesspeople.

[26] Junaidi, I. (2022-b). Proposal to raise drug prices rejected. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1705331.

[27] Mehmood, K. (2022). Cabinet rejects increase in medicine prices. The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2376471/cabinet-rejects-increase-in-medicine-prices.

[28] Khan, U. (2022). PM Shehbaz turns down summary to increase medicine prices. Samaa. https://www.samaaenglish.tv/news/40016924.

[29] Dawani, K. & Sayeed, A. (2020). Anti-corruption in Pakistan’s pharmaceutical sector: A political settlement analysis. Working Paper 25. Anti-Corruption Evidence (ACE) SOAS Consortium. https://ace.soas.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/ACE-WorkingPaper025-PakistanPharma-200701.pdf.

[30] Government of Pakistan. (1976). The Drugs Act 1976. https://www.dra.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Drugs-Act-1976.pdf.

[31] Dawani, K. & Sayeed, A. (2020).

[32] Dawani, K. (2020). Why amending Pakistan’s drug pricing policy is a mistake. Anti-Corruption Evidence (ACE) SOAS Consortium. https://ace.soas.ac.uk/why-amending-pakistans-drug-pricing-policy-is-a-mistake/.

[33] Mehmood, S. (2022-a). Regulating the Pharmaceutical Industry: An Analysis of the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP). Chapter 2. Book 48 Evaluations Of Regulatory Authorities Government Packages And Policies. PIDE. https://pide.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/book-48-chapter-2-regulating-the-pharmaceutical-industry-an-analysis-of-the-drug-regulatory-authority-of-pakistan.pdf.

[34] Mehmood, S. (2022-a).

[35] Government of Pakistan. (2022). The Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP) Act 2012. https://www.dra.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/DRAP-2012-_As-Amended-till-Feb-2022.pdf.

[36] Dawani, K. & Sayeed, A. (2019). Pakistan’s pharmaceutical sector: issues of pricing, procurement and the quality of medicines. Working Paper 12. Anti-Corruption Evidence (ACE) SOAS Consortium. https://ace.soas.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ACE-WorkingPaper012-PakistanPharmaSector-190801.pdf.

[37] Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan. (2013). Statutory Regulatory Order (SRO). National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination Division. Government of Pakistan. https://www.dra.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/SRO-707-2013.pdf.

[38] Dawani, K. & Sayeed, A. (2019).

[39] Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan. (2013).

[40] Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination. (2018). Drug Pricing Policy 2018. Government of Pakistan. https://www.dra.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Drug-Pricing-Policy-2018-_As-amdended-till-August-2021.pdf.

[41] Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination. (2018).

[42] Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination. (2018).

[43] Dawn. (2022-b). Production resumes after 25pc rise in paracetamol rates. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1717119/production-resumes-after-25pc-rise-in-paracetamol-rates.

[44] Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination. (2018).

[45] GlaxoSmithKline Pakistan Limited. (2018). Third Quarter Report 2018. https://pk.gsk.com/media/6175/gsk-q3-2018-report.pdf.

[46] World Health Organization. (2022). Global Health Expenditure Database. WHO. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_profile/Index/en.

[47] Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. (2022). National Health Accounts (NHA) Pakistan 2019-20. Ministry of Planning Development & Special Initiatives. Government of Pakistan. https://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/national_accounts/national_health_accounts/NHA-Pakistan_2019-20.pdf.

[48] Mehmood, S. (2022-b). Ameliorating Drug Shortages in Pakistan. Policy Viewpoint. No. 37. PIDE. https://pide.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/pv-37-ameliorating-drug-shortages-in-pakistan.pdf.

[49] Mehmood, S. (2022-a).

[50] Dawani, K. (2020).

[51] Hussain, B. (2022). Drug shortage hits Karachi as demand exceeds supply. Business Recorder. https://www.brecorder.com/news/40196392.

[52] The Express Tribune. (2022-b). Medical supplies shortage. The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2374958/medical-supplies-shortage.

[53] The Express Tribune. (2022-b).

[54] Abbas, D. (2022). Common medicines disappear from market. The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2375858/common-medicines-disappear-from-market.

[55] Mehmood, S. (2022-a).

[56] Dawani, K. & Sayeed, A. (2019).

[57] Mehmood, S. (2022-a).

[58] World Health Organization. (2020).WHO guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies, second edition. Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240011878.

| [59] Babar, ZUD. (2022). Forming a medicines pricing policy for low and middle-income countries (LMICs): the case for Pakistan. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice 15, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-022-00413-3. |

Ali Saood

Ali Saood is a Policy Associate at Tabadlab. Currently, he is working on research and advisory projects focused on public and private sector engagements to improve the Public Health ecosystem. His past work experience includes policy analysis, developing institutional strategies, researching Digital Humanities Tools, and strategizing supply chains. He is interested in exploring mechanisms that mobilise private sector to achieve development outcomes. Ali holds a Master's in International Development from University of Edinburgh and Bachelor's in Business Administration from IBA Karachi.