On August 22, in the midst of the devastating floods that shook Pakistan this monsoon season, the country’s mobile network – both call and data – failed.

This failure in the country’s foundational digital layer was triggered by the floods, but the real problem goes deeper. The floods have exposed the fragility of Pakistan’s telecommunications infrastructure, and the weaknesses of the broader structural environment within which mobile networks operate.

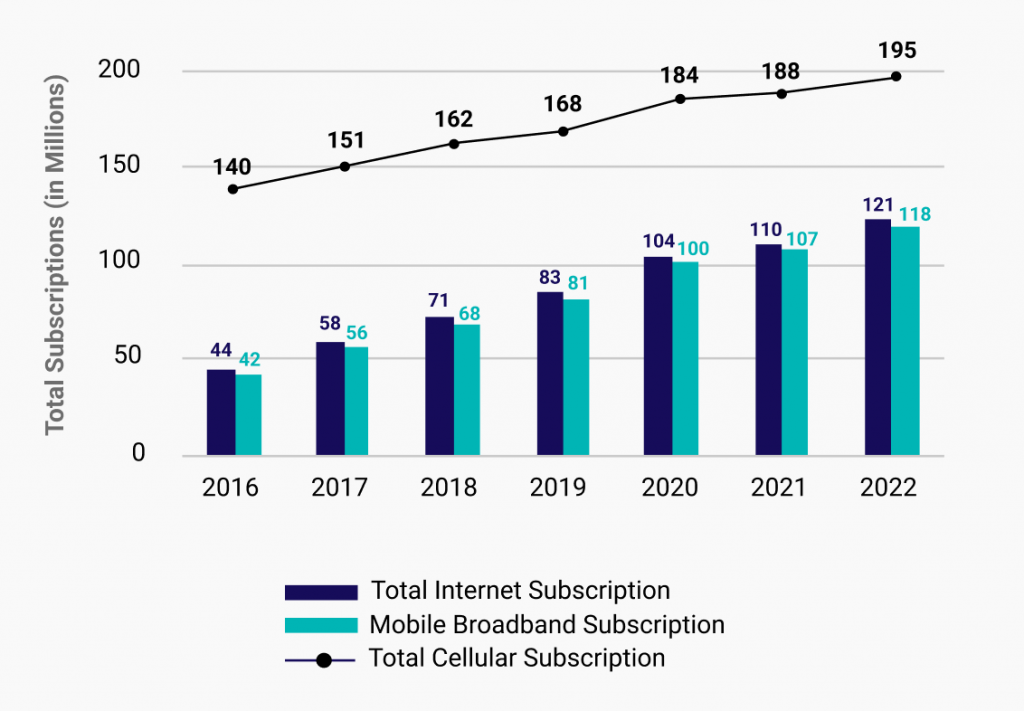

Without immediate intervention, the industry is prone to collapse. Such a collapse would devastate not just Pakistan’s broader digital transformation journey, but also the lives of Pakistan’s 195 million telecommunications subscribers and 123 million broadband subscribers.[1]

Telecommunications capabilities went down immediately after the floods

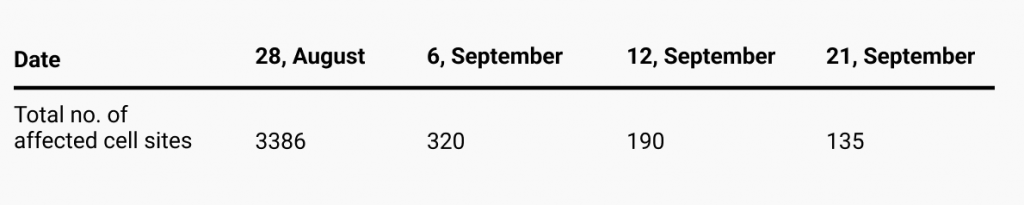

In the wake of the floods a total of 3386 cell sites were marked inactive across flood-impacted provinces, resulting in suspensions in mobile connectivity and internet services. Because of this:

- Thousands of flood victims have intermittent connectivity, making it difficult for them to contact loved ones or reach out to relief teams.

- Relief teams report difficulties in communicating with concerned departments due to connectivity issues.

To overcome short-term connectivity barriers, companies are generously offering their customers free on-net voice call services. However, these solutions are short-term band-aids to a bigger set of issues.

Source: PTA and New York Times

Flood damage will have a lasting impact on core telecommunications infrastructure

Connectivity failures at the time of the floods are largely associated with structural and technical damages to core infrastructure. The two primary infrastructure pieces are:

Fibre optic cable – The country has six main fibre optic cables covering 130,000 km to 150,000 km powering both fixed broadband as well as mobile broadband in the country.[2]

Cell towers– As of 2022,there are approximately 50,633[a] cell towers in Pakistan. Only 5% of towers are connected to the fibre optic network which is significantly lower than the international standard of 40%.[3]

In the aftermath of the floods, several cuts in the fibre optic network were reported making several cell sites inactive. While the PTA shared that the total number of inactive cell sites were reduced from 3,386 to 135 many of the remaining inactive sites – specifically those in Balochistan and Sindh – are still underwater and cannot be accessed for repairs.[4]

These disturbances across the cell site transmission network have affected the voice and data services of multiple MNOs (Mobile Network Operators) including Ufone, Zong, and Telenor.

Relief efforts are likely to further worsen this picture. Pakistan’s fibre optic network runs under highways and railway tracks, many of which were washed away because of heavy flooding. Diverting water flow requires digging roads and building trenches using heavy machinery, which can create further damage to the fibre optic network. As we have already seen, damage to one part of the fibre optic cable can digitally paralyse a much greater area since limited alternatives are available.

The limitations of our telecommunications network are becoming increasingly obvious

While the floods’ impact on infrastructure is undeniable, connectivity interruptions over the last few weeks are both a consequence of the floods, and a reflection of the fragile state of our telecommunications sector. Had the underlying infrastructure been more robust, the industry would have been much more resilient in the face of a single large-scale event. However, the issues go deeper and have been materialising for some time.

Despite significant demand for mobile broadband services – which has translated into 108% growth in subscriptions over the last five years – serious issues plague the telecommunications sector. Beyond the floods, a digital emergency is at hand for all actors in the space.

Source: PTA

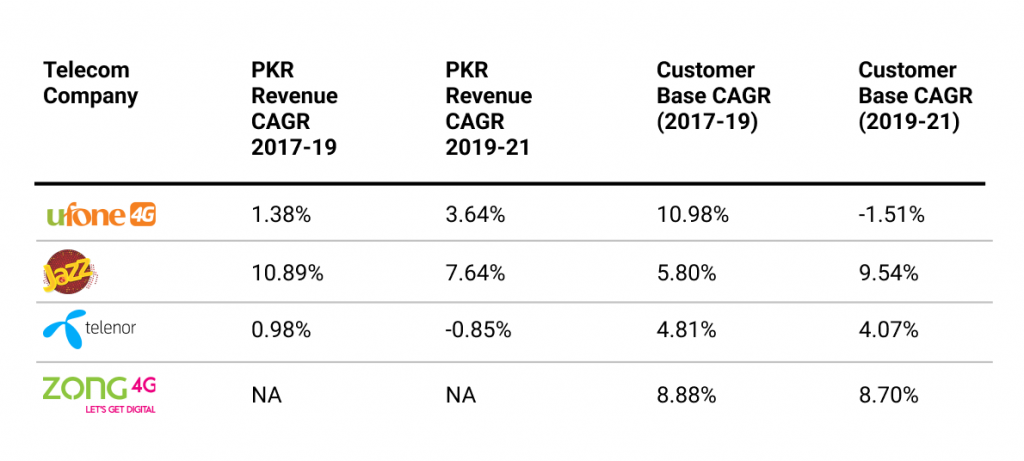

Financial results from the last few years show that, though both top line revenue and the customer base are largely increasing, the rate of growth has slowed down for almost all major players.[b]

Source: Annual Financial statements for the MNO’s

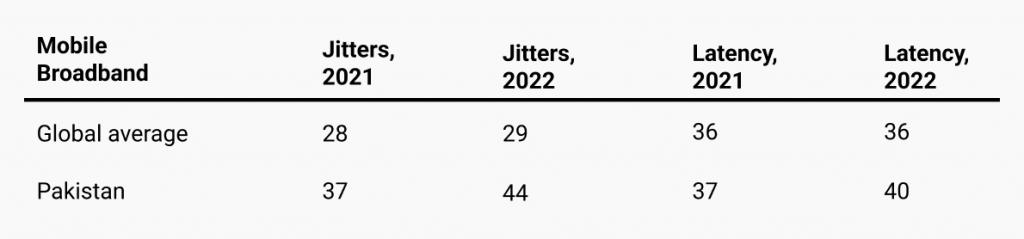

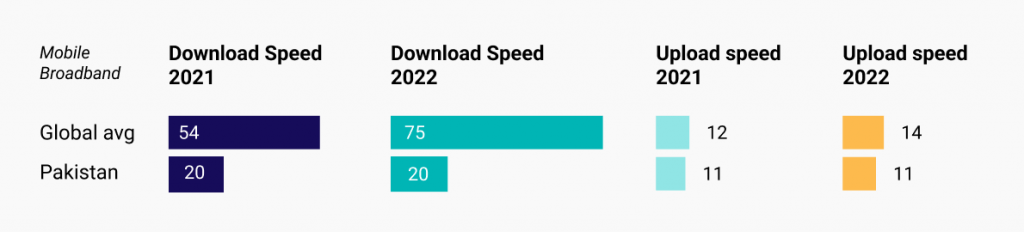

Like the big MNOs, users are also suffering, with individuals experiencing decreased quality mobile broadband: jitters rose by 19%, and latency has also increased by 8%. This means that not only are there higher fail rates, but people on the ground are also experiencing slower internet speeds in real terms.

Source: Speed Test Global Index

In a context where average download and upload speeds are diverging increasingly from global averages, the declining customer experience of mobile broadband is a serious concern. In 2022, Pakistan’s ranking on the Speed Test Global Index for mobile broadband went down 7 rankings from 113 to 120 in the world.[5]

Source: Speed Test Global Index

Systemic conditions have brought the telecommunications sector to its knees

As the data shows, the telecommunications industry is not just fragile and prone to collapse in the face of natural disasters. It is also on the decline both from a business and user point of view. Systemic conditions that have led to this state are as follows.

Investments favour mobile broadband to the detriment of core infrastructure development

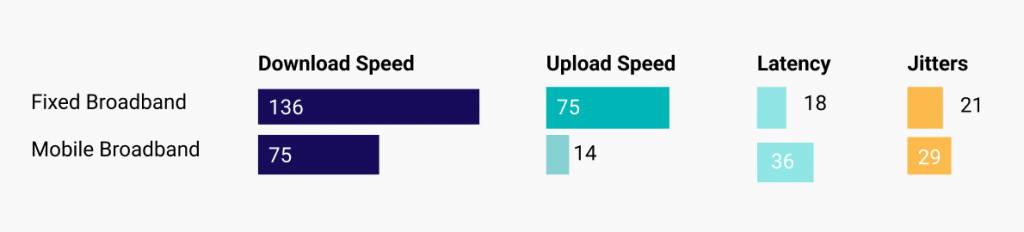

Pakistanis disproportionately favour mobile broadband over fixed connections when it comes to accessing the internet. In fact, mobile broadband subscriptions comprise 97.7% of all internet subscriptions.

Such high consumer demand means that mobile broadband is a very lucrative service from a revenue perspective. Additionally, mobile broadband infrastructure is relatively cheaper to deploy in comparison to fixed broadband infrastructure. The high-revenue/low-cost combination skews both MNO and government investment incentives to prioritise mobile over fixed broadband services.

Unfortunately, the current state of investment will not help Pakistan’s connectivity landscape in the long-run – either in terms of reach or quality. Even if mobile broadband continues to be prioritised, reach and quality are affected by the backhaul connectivity of cell sites, which is powered by core fixed broadband infrastructure. Moreover, to truly capture the benefits of the internet, fast and stable connectivity is critical, and this will only come with increased fixed broadband deployment. As such, any sustainable improvement and upgradation in connectivity requires synergetic investment in both mobile and fixed broadband.

Source: Speed Test Global Index

Commercial spectrum availability is limited.

As of 2021, only 274 MHz – which is one-third of the total spectrum – has been made available for commercial auction and acquisition.[6] The limited and sporadic allocation of spectrum has primarily resulted from the government’s prioritisation of short-term revenue maximisation over promoting a large-scale shift to digitisation.

For the industry, restrictions on spectrum availability results in a) higher purchasing costs, and b) increased pressure to provide and upgrade services to an expanding consumer base within the limited available capacity. For customers, this means having to deal with high prices, reduced network coverage, and poor quality.

Poor macroeconomic conditions have raised operating costs for all MNOs.

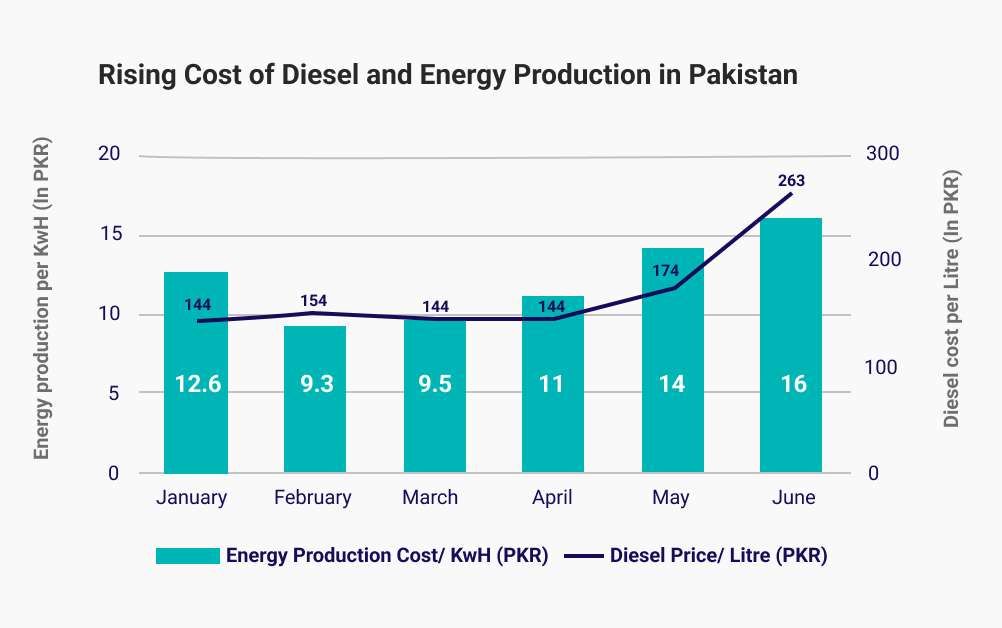

The country’s electricity costs are on the rise. This has impacted the OPEX for all MNOs, especially in terms of tower costs[c]

Source: Pakistan State Oil & NEPRA

Tower costs have been driven even higher by continuous power outages that have forced MNOs to fall back on alternative power sources to ensure unhindered connectivity. Backup power is typically assured via diesel generators which are not only expensive to acquire and maintain, but also require constant refuelling. With the cost of diesel soaring by 82% – from PKR 144 to PKR 263 – in the first six months of 2022, MNO operating costs are under additional strain.

Connectivity is treated as a luxury and not a fundamental right.

The treatment of the telecommunications industry as a revenue generator means that it is subject to several fees and charges; these include:

- Spectrum and service charges – The current licensing and renewal framework for MNOs is very complex; fee and renewal time periods vary across different providers. Apart from these inefficiencies, fees have increased significantly over the last few years. In the last decade, the cost of spectrum fees for 1 MHZ spectrum in the 1800 band rose 388% in rupee terms, going from PKR 1.27 billion to PKR 6.65 billion.[7] As a result, almost 10% of the total revenue generated by major MNOs is being spent on spectrum expenditures. Since the spectrum fee is set in US dollars it does not account for rupee devaluation and general volatility.

- Taxation – In the last seven years, customs duty on telecommunications equipment has increased from 5% to 20%.[8] Additionally, since 2015, imported equipment is also liable for sales tax which currently stands at 19.5%.

On the user end, customers also have to contend with high taxation. In 2022, withholding tax on mobile use rose 50%, increasing from 10% to 15%. Total taxation (withholding and GST) on consumers equals 34.5%.[9]

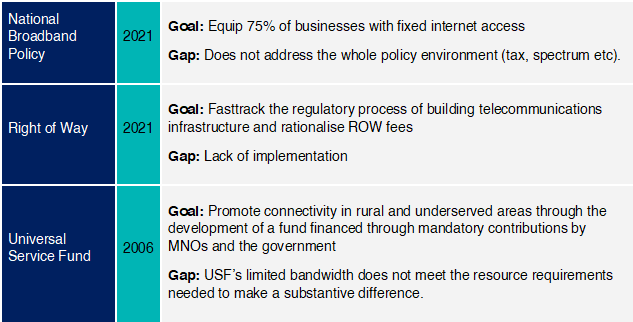

The public policy ecosystem is not fit for purpose.

Several policy and programmatic initiatives have been launched under MoITT to help steer the telecommunications sector. However, there has been limited success to date given the poor execution/implementation of the developed policies.

Source: Tabadlab policy analysis

Charting a path forward: strengthening Pakistan’s digital ecosystem

Pakistan’s underlying infrastructure is vulnerable – given the realities of accelerating climate change, disaster events like the 2022 floods, are no longer a one off, and are likely to recur year after year. Creating a resilient and robust telecommunications sector that can handle such events is critical for both immediate relief efforts, and also for our long-term digital viability.

As Pakistan aims to progress along its digital transformation journey all actors need to radically change how they view and treat the telecommunications sector. Telecommunications forms the base layer of the entire digital ecosystem; a strong ecosystem is reliant upon a strong core. Unless we collectively tackle the existing range of issues, Pakistan’s digital ecosystem will be permanently compromised.

A holistic approach to digital connectivity is called for, which at a minimum should do the following:

1. Ensure resilience – To ensure sustainability the broader narrative needs to be focused on shifting from post-event disaster relief to creating foundational resilience, keeping digital connectivity at the core:

a. Build a telecommunication resilience framework – While a general resilience framework does exist (National Monsoon Contingency Plan 2022), there is no connectivity specific one. All future planning regarding the growth of the telecommunication industry must include a framework for the response and restoration of mobile and internet services in the face of calamities. Timely and accurate identification of potential failure in cell/optic cable sites and a well-thought-out strategy for repair and restoration can be critical in mitigating the damage to connectivity.

Building resilience in the face of adversity: The Malaysian Case

Malaysia is no stranger to devastating flash flooding. An average of 163 annual flood occurrences have been reported in the last two decades, with over 223 flooding events being reported in 2021 alone. The recurrent flooding has propelled Malaysia to work on resilience strategies to strengthen core infrastructure. This includes maintaining connectivity to ensure targeted and effective relief efforts.

During the recent 2021-22 flood season, 1,028 out of the country’s 22,682 cell towers which serve Malaysia’s 32 million strong population were affected due to power outages and damages caused by rising water levels. Immediate action included dispatching repair teams, and a switch to radio services to maintain communication. The government allocated RM 50 million for flood relief efforts, while the telecommunications sector as a whole invested RM 12 million to repair cell sites, broadband fibre equipment and offered subscriptions waivers to affected customers.

In the aftermath of the recent floods, the Communications and Multimedia Ministry of Malaysia recommended adopting the following measures to further protect telecommunications infrastructure in any future flooding events:

• Build higher platforms for towers, an additional 3 meters at least

• No ground level equipment in flood-prone areas

• Maintain a dispensable power supply in case of electrical failure

• Better emergency alert systems

b. Focus on depth and not just breadth – The survival of mobile and internet coverage amidst a crisis is not only dependent on the area of coverage, but also on the quality of core infrastructure. Examples of this within the context of Pakistan include increasing the fibre to tower ratio, and upgrading telecommunications equipment in line with international standards which increasingly are prioritising miniaturisation and other climate smart measures.

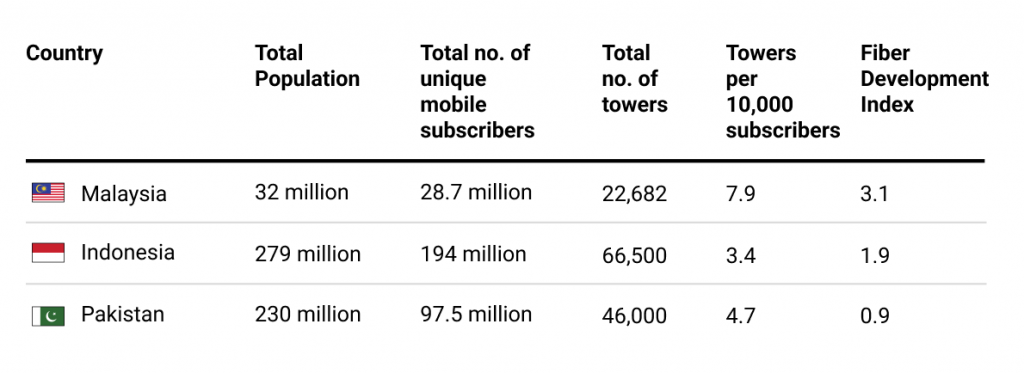

Source: Various GSMA and other reports[d]

2. Treating the telecommunications industry as core public infrastructure – As digital is becoming the new normal, it is important for countries to develop and advance infrastructure that ensures digital connectivity. Under this orientation, digital infrastructure is valued as highly as physical infrastructure such as road networks.

a. Develop a supportive policy environment – Policies must facilitate the sector by creating an enabling environment instead of hindering it. This entails drafting regulations that adequately cater to the needs of both industry and consumers and are also implemented in their entirety.

For instance, a policy needs to be in place to create an effective infrastructure sharing system between sectors through well executed regulations on the use of spectrum, cell towers, cables, and electricity. This can significantly help share the burden of deployment prices as well as operating costs for network operators and promote long term network expansion.

b. Increase Fiscal Support – Investments in the long-term growth of the telecom infrastructure are crucial and need to be prioritised in lieu of short-term fiscal gains. For example, relief on taxation (both consumer and sales tax) is necessary in supporting network expansion by the sector as well as improving affordability of mobile internet and services by the consumers. To provide further relief, the high spectrum fees also need to be revisited and adjusted given the devaluation of rupees.

c. Optimise day to day regulatory control – Regulatory frameworks need to be reassessed and developed for a more efficient identification and redressal system. Operational checks should be fit for purpose and reflect the reality of the context within which MNOs are operating. For example, current monitoring and quality assurance checks on the telecommunications sector have been consistently missed which has led to cyclical fines administered on a weakening industry. As such, it is worth examining the standards themselves to make sure they are responsive to the industry’s needs.

3. Promoting consumer behaviour change for long term benefits – Understanding and facilitating shifts in consumer behaviour is central to creating demand for more efficient mobile services such as fixed broadband and 5G etc. However, telecommunications companies alone cannot take the burden of shifting consumer demand while also focusing on revenue generation. Their efforts need to be supported by players across the ecosystem.

a. Improve consumer awareness and willingness to pay – MNOs and other relevant actors, must improve awareness among consumers about the criticality of digital to their daily lives. Unless people are aware of the benefits of quality connectivity for their social and economic well-being, they will be unwilling to invest in this area. This is important because the long-term viability of the telecommunications sector will eventually require a (likely upwards) revision in the unit model. Unless consumers are made less sensitive to price changes by establishing connectivity as an essential good, the telecommunications sector will not flourish.

b. Fix incentive structures in line with long-term planning – Regulatory and fiscal support to consumers for using digital will help shift people into becoming more digitally connected. Anecdotal evidence suggests that high taxes on telecommunications prevent people’s ability to invest in high quality phones and data packages.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this piece are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of either Tabadlab’s Centre for Digital Transformation or Tabadlab Private Limited.