Download a pdf version here.

Background and Context

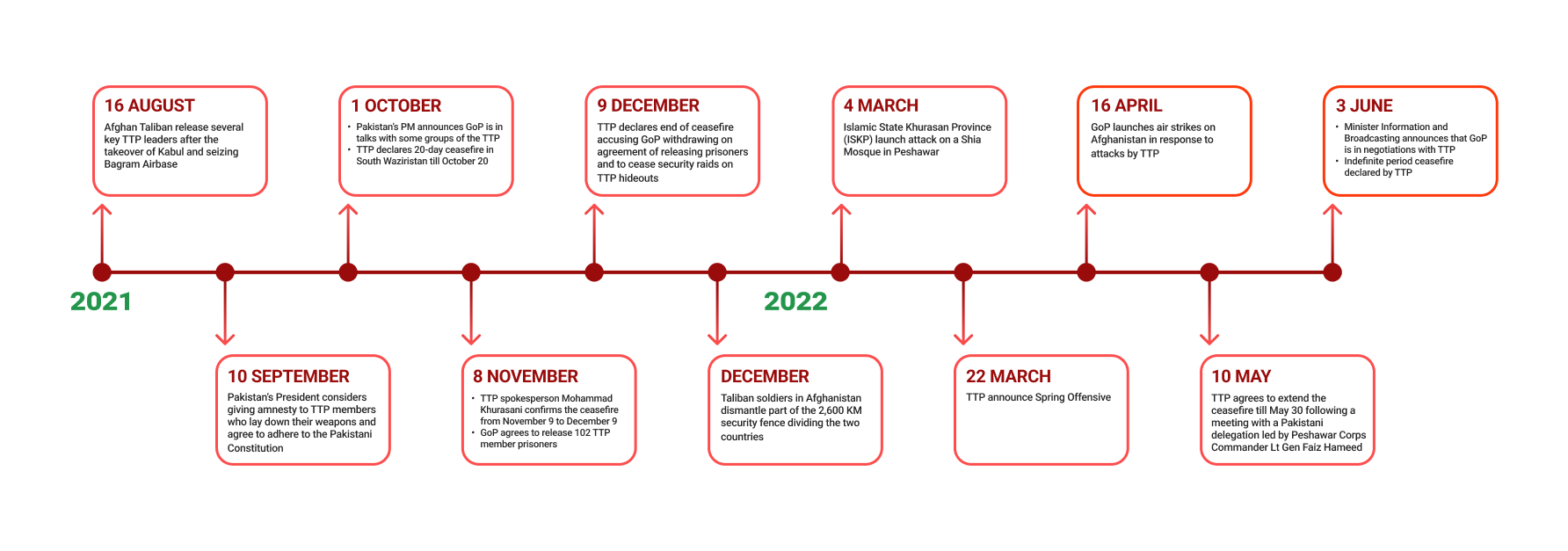

The Government of Pakistan (GOP) and the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) have been pursuing a peace process since October 2021. This followed the Afghan Taliban or the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) taking control of Kabul in mid-August 2021[i] and the TTP leader renewing his existing allegiance to the Afghan Taliban shortly afterwards.

The parties have agreed to a temporary ceasefire until mid-June after which they will resume consultations, though some sources suggest that the duration of the ceasefire is indefinite.[ii] The talks, reportedly led by XI Corps Commander (and former DG ISI) Lieutenant General Faiz Hameed, were brokered by the IEA and eventually mediated by interim Afghan Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani.[iii] This was the second time the two sides have engaged in negotiations in the month of May 2022, with the most recent talks being the first time the GOP formally acknowledged the process.

A central point of contention in the negotiation process for both sides is the status of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan, and the treatment of the Newly Merged Districts (NMDs) of the former Federally Administered Tribal Area (FATA). This development is in parallel to the Election Commission of Pakistan’s (ECP) recent announcement of the completion of its district demarcation process, which has identified 266 constituencies, down from 272, owing in part to FATA’s change in status.[iv] This makes the peace process an important event in the constitutional and political process through which the NMDs are being normalized as Pakistani territory—a process that holds wider implications for state building and inclusion in Pakistan.

TTP continues to remain a considerable threat to Pakistan’s safety and internal stability as a major contributor to the 294 recorded terrorist attacks in 2021 alone, a 56% rise compared to the previous year.[v] The vast majority of these terrorist attacks have targeted military personnel and border check posts. Pakistan has also experienced an increase in terrorist incidents conducted by separatist terrorist groups operating in Balochistan. The recent terrorist attack in Karachi that claimed the lives of four, including three Chinese nationals, added to growing pressure on Pakistan as a key counter terrorism partner for China.[vi]

With the TTP retreating to hideouts in Afghanistan, Pakistan’s frustrations have grown as calls for curbing the group and halting their activities were met with inaction by the IEA. GOP reportedly conducted targeted airstrikes in Afghanistan territory (in the Kunar and Khost provinces), a move that represents a tactical escalation and complex strategic implications. The IEA and their willingness to support Pakistan after such strikes puts the sustainability of such escalatory measures in doubt. Other key considerations are civilian loss of life, the lack of precise intelligence, and the reaction of the ordinary citizen of Afghanistan. Additionally, it is not clear that TTP ranks themselves would be any likelier to surrender to Pakistan in the overhang of such strikes.

In summary, communication has opened between GOP and the TTP after several years, facilitated by the Afghan Taliban. This presents a major shift in Pakistan’s policy of targeting TTP hideouts and leadership, especially in the tribal areas.[vii] The peace process has led to the temporary ceasefire, the release of dozens of TTP terrorists from Pakistani jails[viii] and a significant reduction in TTP attacks in Pakistan, according to the latest UNSC Monitoring Team Report.[ix]

Figure 1: A Timeline of Events Since the Afghan Taliban Came to Power in Kabul

Figure 1: A Timeline of Events Since the Afghan Taliban Came to Power in Kabul

Current Status of Negotiations in the ‘Peace Process’

Talks between the TTP and GOP were only recently acknowledged publicly by the GOP. In a public address on June 3, 2022, Pakistan’s Federal Minister for Information and Broadcasting Pakistan Marriyum Aurengzeb made a reference to the talks, shortly after the TTP had reportedly extended the ceasefire for an indefinite period.[x]

The TTP’s has several demands, the most pertinent of which are:

- Restoration of the traditional semi-autonomous status of several of Pakistan’s north-western districts. This means the reversal of the 25th Constitutional Amendment of 2018 and an end to the integration of the NMDs into the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province.

- Discontinuation of Pakistani military outposts in the NMDs, implying a complete withdrawal of troops.

- Release of 102 commanders and fighters in Pakistani prisons and presidential pardon to two key militant commanders, TTP Swat leaders Muslim Khan and Mehmood Khan.

- Enforcement of TTP’s version of the Shariah Law through the Nizam-i-Adl regulation in Malakand division, citing their rejection of the Pakistani constitution as un-Islamic.[xi]

- Freedom of movement for the TTP’s members and activities in Malakand division.

Meanwhile, the GOP has put forth its own set of demands.

- The complete dissolution of the TTP, thereby formally disbanding and disengaging from other militant groups.[xii]

- Second, for the TTP to renounce their arms and use of violence and instead to officiate as a non-violent political party and respect constitutional norms of the GOP.[xiii]

It is important to note that the TTP is also under immense internal pressure by members’ families for successful and peaceful repatriation to Pakistan.[xiv]

Key Stakeholders in the Peace Process

The Government of Pakistan (GOP) is an integral actor in this negotiation process, and it appears to be in a position of relative strength. It benefits from good relations with the IEA and has exerted pressure on Kabul to bring the TTP to the negotiating table after a significant rise in the number of attacks by the latter, and repeated calls by Pakistan to curb the group. Once the first installation of the ceasefire was violated by the TTP with another set of attacks on March 30 and April 14, the Pakistani military reportedly conducted unprecedented airstrikes in eastern Afghanistan, underlining that Pakistan was going to go after the TTP, regardless of where it was located.[xv] Since then, another indefinite ceasefire has reportedly been agreed upon—evidence to the relatively powerful position that Pakistan holds at the negotiating table.

However, this advantaged position also imposes on the GOP, the responsibility to conduct itself in accordance with the demands of being a mature state and a major regional power. This implies a truly peaceful, non-disruptive, and bloodless peace, that secures the lives, safety, and well-being of both Pakistani and Afghan citizens—for now and the future. Anything short of this would be a failure. There appear to be strategic advantages to concede to a minority of the TTP’s current demands, to ensure the continuation of the ceasefire and reduction in the number of TTP attacks in Pakistan. However, this this will have to be a careful balancing act of not conceding to demands that run counter to peaceful outcomes. The decision to publicly disclose the ‘peace process’ must then be viewed as an implicit declaration by the GOP that it intends to uphold its stature and secure these outcomes.

The TTP is at the negotiating table as the sole non-state actor in the process. Its main instrument of negotiation and pressure is violent extremism and terror. Attacks on Pakistani targets, particularly the armed forces, are the primary source of salience for the TTP. The power it holds is in the destruction and loss of life it has caused and can further cause. At least 294 militant attacks were recorded to have taken place in 2021, a 56% increase compared to the previous year, according to the Islamabad-based Pakistan Institute for Conflict and Security Studies (PICSS)[xvi] of which most were claimed by the TTP.

The group has coalesced after a period of significant splintering, absorbing many additional smaller groups during this resurgence[xvii]. While it may appear as a monolith, there are internal groupings, divisions, and cleavages. Both the GOP and the IEA need to consider the role of the various constituent elements of the TTP, the degree to which there is unity, and how the fallout of break off factions still committed to terrorism will be dealt with, in the scenario that a peace deal is eventually reached.

The impact of the TTP’s violent terror activities on the lives of ordinary citizens, governance, and the economy in the NMDs and beyond requires deep reflection and deliberation. The TTP’s assumption of a seat at the table in negotiations with the very state it has waged war upon represents a significant political event—both nationally for Pakistan, and regionally for the South and Central Asian regions.

A key consideration, beyond the TTP itself is how the TTP will distance itself from Da’esh, or the so-called Islamic State in the Khorasan Province (ISKP). Da’esh’s escalated terrorist activities in Pakistan represent a different set of challenges to Pakistan than what the TTP posed, but a TTP-ISKP nexus would be a problematic development for both the GOP and the IEA.[xviii]

The IEA is playing the role of the meditator in the negotiations and seems to be trying to balance its relations with the Pakistani state as well as maintain good posture with the TTP. Appeasing the GOP is essential to relieve the regime from external pressure from a key ally state and curb the possibility of further airstrikes. Sirajuddin Haqqani, the acting Afghan Interior Minister seems unwilling to coerce the TTP[xix]. His areas of influence and operation have been the eastern and south-eastern Afghan border provinces, now a safe haven for TTP cadres that have fled the Pakistani security net.[xx]

Securing a peace deal for the TTP with Pakistan would also mean that the IEA would forestall the potential of a disgruntled and desperate TTP joining forces with Da’esh—a clear and present threat to the Afghan Taliban’s monopoly over violence in Afghanistan.[xxi] Therefore, a peace deal represents a positive tactical outcome for the IEA.

Finally, the IEA’s long term relationship with Al-Qaeda (AQ), which was supposed to have ended with the Doha Agreement, seems to continue to have life.[xxii] Key members of the AQ leadership are living in eastern Afghanistan as the Taliban’s guests, and the most recent UN Security Council Resolution 1267 monitoring report concludes that, “Afghanistan has the potential to become a safe haven for Al-Qaeda and a number of terror groups with ties to the Central Asia region and beyond.[xxiii] A successful negotiation and peace deal between the GOP and TTP would then serve not just to cut off the potential of TTP joining forces with other terrorist groups (like Da’esh and Al Qaeda) but also serve as evidence to IEA’s enduring commitment to the Doha Agreement.

Pakistani citizens belonging to the NMDs, Malakand division, and neighbouring areas that are most susceptible to attacks in KP and Balochistan, could be beneficiaries of a new era of peace, security, and stability. But the process and outcomes of these negotiations needs to clearly demonstrate that their rights and well-being are sacrosanct to the GOP. A delegation of 57 native elders, parliamentarians, and political actors represented the people’s stakes and interests in the peace process,[xxiv] demonstrating their importance as agents in the political and security deliberations that affect their homeland and the region beyond.

The involvement of such a delegation is a welcome development, but the political and legal salience of such engagement is contentious. On June 11, Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari tweeted, that his party, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), believes that with respect to the talks with the TTP, “PPP believes all decisions must be taken by parliament”.[xxv] This is a perfectly reasonable contention, given the vitality of the issues at stake in the negotiations: sovereignty, territorial integrity, monopoly over violence, and constitutional norms.

However, while the PPP’s contention in this regard may be necessary, it is still not a sufficient condition for the people’s ownership over the process. Several other groups will also be critical to the outcome, perhaps most notably, the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM), an umbrella body working for the protection of the people of the tribal belt. The buy-in of communities, including groups like the PTM is essential both for the longevity and vitality of the process, and to ensure that unhappiness with an eventual peace deal does not derail or undermine the eventual deal’s legitimacy.

The people of Afghanistan, especially those inhabiting the borderlands of Afghanistan’s eastern provinces, are just as important to considerations of livelihoods and safety since communities at the borders would be significantly vulnerable to any unrest between GOP and the TTP. This is a live issue as up to 4,000 TTP fighters have been reported to be holed up in the Afghan provinces bordering Pakistan, making them the largest group of foreign fighters-based in the country.[xxvi]

The US and the international community, as the continued patronization, engagement with, and sheltering of the TTP effectively puts the IEA in violation of the Doha Agreement. In particular, the agreement specifically prohibits the IEA or Afghan Taliban from facilitating or supporting any groups or helping them with coordinating, recruiting, training, and fundraising through the use the soil of Afghanistan to threaten the security of the United States, its allies, or any neighbouring countries.

Potential Implications

Given the historical, political, and constitutional importance of the ‘peace process’, and Pakistan’s strategic positioning and utmost responsibility for a favourable outcome for itself and the region beyond its own territory, it is crucial to establish the plausibility (or lack thereof) and viability (or lack thereof) of the TTP’s demands.

- Can Pakistan accept the discontinuation of Pakistani military outposts in the NMDs (formerly FATA), meaning a complete withdrawal of troops?[xxvii]

Consideration: There is a marked difference between military presence along the border for boundary control, and presence in the tribal belt for operations and other paramilitary functions. The former will continue to be the case for the foreseeable future. The TTP wants both to be reversed. Following the integration of the NMDs into the KP province, a reduction in military presence and operations may be feasible. However, the complete withdrawal of the military may not be.

Handing over to the civilian administration should be the end goal but will take time, require deep and unprecedented cooperation and trust between military and police authorities, and naturally entail significant overlap. Any such transition must be resourced and paced in accordance with the federal and provincial government’s abilities and appetites, and not under duress from the TTP. The sooner the conditions are prepared for such a transition, the more beneficial for the NMDs, the GOP, and the military.

The military may also have a role in mitigating the wider economic and social impacts of Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad and sustained military deployments in Miranshah and Mir Ali on local populations. Until improved integration and corresponding human and physical development in the region takes place, and the civilian administration can step in, the military may represent the state’s only option to engage the region effectively. Such commitments have been officiated under the 25th Amendment which lays out a series of steps for full integration, such as the rehabilitation of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), investments in infrastructure (both housing and commercial reconstruction), and service delivery of socio-economic development programs.

Any possibility of withdrawing deployed military (on borderlands or in NMDs) should be the result of an internal calculus facilitated by resource availability, improved economic and social indicators, the strict enforcement of the rule of law in the region, and regional cooperation by responsible state actors, and not the result of appeasing a terrorist group like the TTP.

- Can Pakistan accept the restoration of the traditional semi-autonomous status of several of Pakistan’s north-western districts?[xxviii] This would mean a ‘reversal’ of the 25th Constitutional Amendment of 2018 and an end to integration of the tribal areas of former FATA into the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

Consideration: This is arguably the central point of contention in the negotiations as it potentiates an issue of the status and treatment of the NMDs. On May 31, the ECP announced the completion of its district demarcation process. The ECP identified 266 constituencies, down from 272, owing in part to FATA’s change in status, and as remarking of the constituencies comprising the new districts (former agencies).

A reversal of the integration would be first and foremost a constitutional and democratic violation, and a complete betrayal of the trust of the people of the NMDs, notwithstanding the many reservations and protestations at the merger. This also presents an urgent case for stronger state-society relations that have yet to be fully cultivated between the GOP and the people of the NMDs.

The reform in sub-national boundaries and integration between ex-FATA and the rest of Pakistan was a monumental decision to have been taken by the will of the people and the state, finally integrating, and ideologically aligning both land and society of the NMDs.

Therefore, such a concession to the TTP would be seen as effectively ceding control of the region and its people to the TTP. Said reversal has alarming ramifications not only for governance and protection, but also the already glacial process of building state-society relations in what was once a territory neglected by the state, governed by the draconian colonial Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR), and devastated by both terrorism and counterterrorism operations.

- Can Pakistan release 102 commanders and fighters in Pakistani prisons and grant a presidential pardon to two key militant commanders, TTP Swat leaders Muslim Khan and Mehmood Khan?[xxix]

Consideration: This demand has been an exception insofar as it has been reportedly accepted by the GOP—which has released the two key TTP leaders recently.[xxx] However, prisoners are a finite bargaining chip, their release for negotiation purposes is not a viable long-term tool nor solution, and should be contingent upon established rehabilitation.

- Can Pakistan accept the enforcement of TTP’s version of the Shariah Law through the existing Nizam-i-Adl regulation in Malakand division, citing their rejection of the Pakistani constitution as un-Islamic?[xxxi]

Consideration: The Shariah Nizam-i-Adl Regulation, 2009 (Order of Justice) is operational in Malakand division since April 2009 – a regulation that was passed by Pakistan’s central government that formally established Sharia law in the Malakand division and is technically still in effect.[xxxii] Additionally, the process of integration set by the 25th Amendment necessitates the establishment of elected local bodies and introduction of judicial reforms to mainstream both the parliamentary and judicial processes in the region.

Hence, any degree of acceptance of this demand to enforce TTP’s own will in law and justice would imply a parallel system of governance, and in the worst-case scenario, no governance by the Pakistani state. For the state, it means complicating the terms and existential spirit of the integration of the NMDs, as it would create a further separation of governing laws and consequently run the risk of non-constitutional institutions and figures of agency that could exercise the implementation of those laws. Such a dual model would imply a violation of the primacy of the constitution (which officiates integration at all levels) and the boundaries of citizenship (who is and is not considered a citizen of Pakistan).

For the society, communities, and the people of Malakand, all considerations above are significant in how they not only identify beyond ethnic and sub-national lines, but also how they perceive and engage with the state. First and foremost, it is problematic if either the TTP or the GOP are the only actors deciding how society, law, and governance is to be conducted in the Malakand division, without the active and uncoerced participation, deliberation, and decisive power of its residents.

- Can Pakistan accept freedom of movement for the TTP’s members and activities in Malakand division?

Consideration: The Fourth Schedule of the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) 1997 tracks and monitors suspect individuals that the state believes pose a threat to the public, and need to be monitored, categorized, and observed. As recently as 2019 and 2021, reports have surfaced of TTP members being placed on the fourth schedule.[xxxiii] [xxxiv] Therefore, complete freedom of movement for the TTP is conducive neither to the livelihoods of communities and the people of the region nor to the GOP’s governance of a recently integrated region. Given the TTP’s historic existential fight with the Pakistan military, state, and people—this would not be an advisable outcome.

The Way Forward

The combined demands of the TTP outlined in the section above imply a clear goal: the TTP want complete command and control of the Malakand division, to move and operate in it unimpeded by military presence, to enforce their version of Shariah Law on a subset of the Pakistani people, and to see a return to freedom of their most violent members. Acquiescing to their demands effectively means ceding a portion of sovereign Pakistani territory to a recognized, tactically weak, and ideologically and existentially opposed non-state actor. It also undermines the military’s historic sacrifices in the long campaign against the TTP.

The following recommendations represent a proposed path forward, as Pakistan finds itself in the eighth month of the negotiations with the TTP. They are made in the spirit of ensuring good governance and safeguarding the lives and livelihoods of the Pakistani and Afghan people.

- Pakistan’s key strength in negotiations is its strong relationship with Kabul. The focus of peace negotiations must remain on extending careful and deliberate dialogue that builds momentum for peace, whilst not alienating the IEA, or the Afghan people. Tactics such as the use of military force (e.g., through airstrikes) or border closures may seem like an attractive pathway to coerce alignment, but they generate high costs, both in terms of civilian suffering and casualties, the aversion of Afghans in general, and the undermining of the IEA.

- The potential release of prisoners is a key issue, which must be made conditional upon the disbanding and liquidation of the TTP and facilitated through the rehabilitation and reintegration programs. It is also important to note that prisoners are a finite bargaining chip and releasing them unconditionally as a goodwill gesture has limited to no benefits for Pakistan.

- The GOP also needs to capitalize on the fact that TTP members’ families have created internal impetus to an end of hostilities. Despite the flurry of small-scale attacks, the TTP is not geared, funded, or capacitated to take on the Pakistani military for an extended period of time. The TTP’s demands are a direct reflection of this. The peaceful and assisted repatriation of their families to Pakistan should be on offer, conditioned, once again, by the disbanding and liquidation of the TTP.

- During this negotiations process and its public disclosure, the Pakistani state must ensure political engagement and participation in the dialogues of the people of Malakand and the NMDs. Beyond gesturing, the inclusion of local voices other than tribal elders and seasoned politicians, especially those of women and young people, must be ensured. The PTM and other less mainstream political groups should be considered for inclusion in the process.

- Despite direct involvement in the ‘peace process’, the GOP must ensure peace-making domestically—especially in the vulnerable areas in the NMDs—to come to ‘consociational’ arrangements with social and political leaders in the tribal areas, address their grievances, and take its most vulnerable citizens into confidence. The risks posed to the GOP as it shares a negotiating table with a violent extremist group must not be neglected. The government must work on ensuring that its own people, especially groups susceptible to disenfranchisement and to the intimidation from groups like the TTP, are not left feeling defenceless and voiceless.

- Continued engagement of tribal leaders and jirgas is essential, as any demand for amnesty must be framed within the context of the two most affected groups of people: the military (already represented), and the tribal elders (a sub-section now represented).

All things considered, the resolution of the matter needs to be swift and conclusive. The longer the talks continue, the more calcified the relative positions will become, resulting in an eventual deadline, and a return to the existing status quo. It is in the interest of the GOP, the TTP, and the IEA to facilitate a timely, well-defined, and strategically viable end to these negotiations.

Endnotes

[i] The Express Tribune. (2022). Govt confirms peace talks with TTP, welcomes indefinite ceasefire. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2359877/govt-confirms-peace-talks-with-ttp-welcomes-indefinite-ceasefire.

[ii] VOA News. (2022). Pakistan, Militants Pause Afghan-Hosted Peace Talks for Internal Discourse Amid Cautious Optimism. https://www.voanews.com/a/pakistan-militants-pause-afghan-hosted-peace-talks-for-internal-discourse-amid-cautious-optimism-/6595633.html.

[iii] The Express Tribune. (2022).

[iv] Khan, I. (2022). NA loses six seats in preliminary delimitation. https://www.dawn.com/news/1692543/na-loses-six-seats-in-preliminary-delimitation.

[v] Pakistan Institute for Conflict and Security Studies. (2021). Annual Report. https://www.picss.net/annual-report-2021/.

[vi] Kishore, S. (2022). Pakistan & TTP: Why Afghanistan-Brokered Peace Talks May Not Achieve Much. https://www.thequint.com/voices/opinion/pakistan-ttp-why-afghanistan-brokered-peace-talks-may-not-achieve-much#read-more.

[vii] Kishore, S. (2022).

[viii] ANI. (2022). Pak releases dozens of TTP prisoners as peace talks continue with banned outfit. https://www.aninews.in/news/world/asia/pak-releases-dozens-of-ttp-prisoners-as-peace-talks-continue-with-banned-outfit20220221042822/.

[ix] United Nations Security Council (2022). Monitoring Team’s Twenty-ninth report. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N21/416/14/PDF/N2141614.pdf?OpenElement.

[x]The Express Tribune. (2022).

[xi] VOA News. (2022).

[xii] VOA News. (2022). Pakistan Sends Team to Kabul to Discuss Cease-Fire. https://www.voanews.com/a/pakistan-sends-team-to-kabul-to-discuss-cease-fire-/6599290.html.

[xiii] Shamsi. (2022). Restoration of FATA: What is the big demand of banned TTP?. https://mmnews.tv/restoration-of-fata-what-is-the-big-demand-of-banned-ttp.

[xiv] United Nations Security Council (2022).

[xv] Gandhara. (2022). Islamabad Hands Over Top Pakistani Taliban Commanders To Afghan Mediators In Bid To Revive Peace Talks. (2022). https://gandhara.rferl.org/a/pakistani-taliban-commanders-handed-over-afghan/31846644.html.

[xvi] Pakistan Institute for Conflict and Security Studies. (2021).

[xvii] Jadoon, A, and Sayed, A. (2021). The Pakistani Taliban is reinventing itself. https://www.9dashline.com/article/the-pakistani-taliban-is-reinventing-itself.

[xviii] Kishore, S. (2022).

[xix] The Express Tribune. (2022). Afghan Taliban’s double game? https://tribune.com.pk/story/2360192/afghan-talibans-double-game.

[xx] VOA News. (2022).

[xxi] The Express Tribune. (2022).

[xxii] VOA News. (2022).

[xxiii] United Nations Security Council. (2022). https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/1267/monitoring-team/reports.

[xxiv] Khan, I. (2022). No major breakthrough yet as jirga returns from Kabul. https://www.dawn.com/news/1693014/no-major-breakthrough-yet-as-jirga-returns-from-kabul.

[xxv] https://mobile.twitter.com/BBhuttoZardari/status/1535615909578084355

[xxvi] VOA News. (2022).

[xxvii] Khan, I. (2022). Islamabad, TTP agree on indefinite ceasefire. https://www.dawn.com/news/1692383/islamabad-ttp-agree-on-indefinite-ceasefire.

[xxviii] Khan, I. (2022).

[xxix] Gandhara. (2022).

[xxx] Gandhara. (2022).

[xxxi] Gandhara. (2022).

[xxxii] Khan, I. (2022).

[xxxiii] Asghar, M. (2021). 18 people added to fourth schedule in Pindi district. https://www.dawn.com/news/1606340.

[xxxiv] Punjab Police. (2022). Strict monitoring of fourth schedulers begins ahead of Pakistan Day. https://punjabpolice.gov.pk/node/6814

To download the complete First Response, click here.

Cover photo: AP Photo/Anjum Naveed