Summary

• Pakistan’s polio infrastructure presents a viable option to kickstart the Covid-19 vaccination services.

• The Polio Eradication Initiative’s (PEI) resources have been repurposed for a Covid-19 response, contributing to testing and information campaigns, utilising its large surveillance network and worker mobilisation at the community level.

• Meanwhile, there is a possibility that the Expanded Programme of Immunization (EPI) infrastructure will be adopted for a Covid-19 immunisation program, benefitting from its nation-wide network of fixed facility centres and vaccinators.

• Both programs have their own strengths and limitations; a viable and strategic plan is to integrate the strengths of the country’s existing polio infrastructures by the immediate implementation of the ‘PEI-EPI synergy’ plan under the National Emergency Action Plan

2020. The government should be mindful that the Covid-19 vaccine deployment does not happen at the risk of compromising other immunization programs and additional required resources must be plugged in, where required.

• For maximum outreach and coverage, a portion of the PEI’s personnel should be mobilised alongside efforts by EPI’s fixed centres, as well as collaborating with private hospitals, labs and clinics.

• Immediate launch of information campaigns through multiple communication channels for maximum inclusivity must be prioritized to address mis-information.

• Coordination with Afghanistan’s Polio Programme is important to combat the risk of non-immunized travellers moving across the national borders.

Identifying the Problem

Governments worldwide have been engaged in strategizing the most contextually suitable and equitable distribution method for the allocation of the much-awaited Covid-19 vaccine. Overwhelmed healthcare systems and the need for post-pandemic economic recovery has raised concerns about the fair, timely and cost-effective provision of the Covid-19 immunization programme upon procurement and the role of the state in supporting socio-economically and geographically vulnerable communities.

In Pakistan, government reports [i] suggest that the Expanded Programme of Immunization (EPI) is planned to be chosen as the system for distribution of the vaccine. EPI provides routine immunisation at the provincial level against numerous diseases such as polio, measles, neonatal tetanus, etc. Meanwhile, polio eradication efforts in Pakistan are mainly operated under the Polio Eradication Initiative (PEI), a body separate from EPI.

Similar to other resource constrained countries, Pakistan’s polio infrastructure presents a viable option to kickstart the Covid-19 vaccination services [ii]. Existing resources of PEI have been utilised to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic in Pakistan. Despite the wide-scale efforts, it is pertinent to note that PEI’s vaccine delivery services suffered from a 4-month suspension while the EPI faced suspension of outreach services, due to which more than one million children missed vaccine dosage for not only polio but also measles and diphtheria [iii]. This is an alarming setback for immunization success in Pakistan which has yet to meet its polio eradication goals, having reported 82 cases of wild polio in 2020 and 147 in 2019 [iv].

The key question is which of the two systems, EPI or PEI, can manage and deliver an equitable, timely and low-cost distribution of the Covid-19 vaccine, or if an integrated approach such as that envisaged under the ‘PEI-EPI synergy’ plan will be better. Several infrastructural strengths and limitations of both programs affect current immunization outcomes which can help assess possible outcomes for Covid-19 immunization and the road-map ahead:

Strengths

PEI’s mobilisation

The high level of community and door-to-door mobilisation by volunteers and lady health workers is a unique and immensely resourceful element of the PEI which has been able to increase vaccine coverage in hard-to-reach populations [v]. Following the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic, physical resources such as vehicles, computers, testing kits, vaccine carriers and 579 polio personnel [vi] were deployed to carry out Covid-19 testing in addition to the provision of PPE kits to medical staff, repairing ventilators, and setting up and monitoring quarantine sites [vii].

Surveillance System

The PEI, through its strong surveillance and monitoring systems, has been able to improve vaccine coverage by prioritising and recognizing high-risk areas such as mega-cities like Karachi and Peshawar and underdeveloped regions in Balochistan and former-FATA [viii]. During the Covid-19 response, efforts to digitize and further strengthen its surveillance system have been prioritized for effective tracing and testing of both polio and Covid-19 symptoms, through the help of 10,000 public and private sector facilities, including general physicians, and traditional healers [ix].

EPI’s Fixed Vaccine Centres

The EPI has an immensely large network of 6,000 facility centres around the country, staffed by vaccinators, which are a strategic option to be used as the physical and logistical infrastructure for the storage and delivery of the Covid-19 vaccine [x], which requires higher cold-chain storage, unlike polio vaccinations. The fixed facilities are an asset to provide permanent logistical support for routine immunisation across urban and rural locations.

Limitations

While the systems of the PEI and EPI are equipped with logistical and management systems, it is important to assess their limitations and potential areas of improvement as possible links to build integration for an effective and holistic Covid-19 immunization program.

Inadequate Distribution of Fixed Centres

While the EPI has a large network of fixed facilities, the geographical distribution of these centres is inadequate. Meanwhile nationally, households often report that vaccine centres are too far or not available for enough hours per week, discouraging them to vaccinate at all [xi].

If the use of fixed vaccine centres is the only means to distribute the Covid-19 vaccine through a digitised appointment system largely prioritising mega-cities, and without the wide mobilisation of polio workers [xii], this inaccessibility will remain unresolved. This is especially concerning for immunization for communities in rural and underdeveloped regions, which have already been receptive to polio workers and vaccinations, as well as producing discrepancies in immunization coverage across urban and rural spaces as well as among provinces [xiii] and in those areas where the rapid movement of people is frequent [xiv].

Shortage of EPI Vaccinators

The EPI’s polio personnel at the provincial level are under-skilled and insufficient to fulfil the required ratio of EPI vaccinators to the public, where each facility on average has only 1.3 vaccinators except in the Sindh province, while the national target is set at 2 vaccinators per centre [xv]. Such shortage is immensely detrimental not only to service provision but also trust-building in communities, the lack of which has resulted in persistent refusal to polio and other routine vaccines in Pakistan.

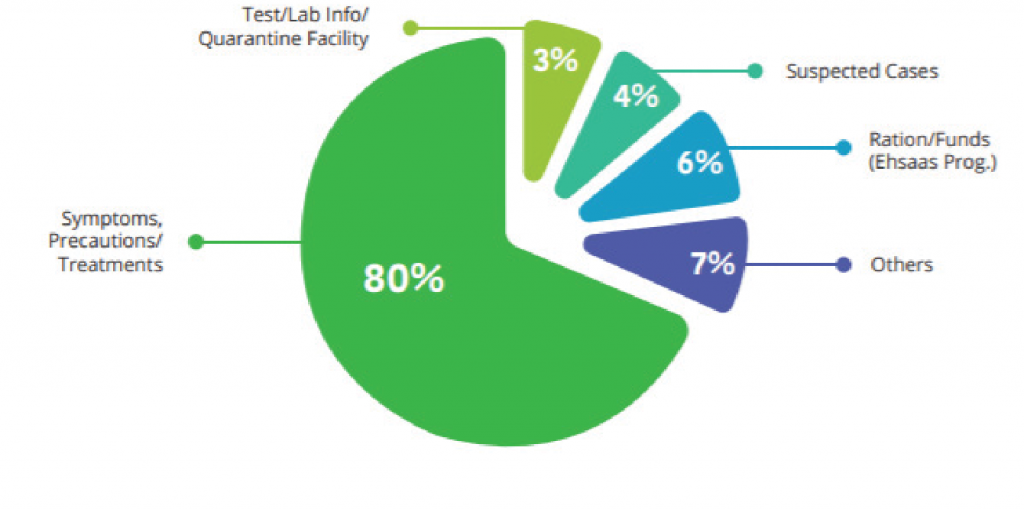

Misinformation

The anti-vax sentiment is a central contributor to persistent polio cases in Pakistan; in contrast to the commonly perceived notion that this sentiment may only be prevalent in rural areas, refusal cases have also been recorded from educated groups in cities [xvi]. Misinformation regarding the Covid-19 virus is also spreading whereby people are questioning the existence of the virus and potential vaccine [xvii]. A recent survey by Ipsos reports that 40% of Pakistanis are apprehensive about receiving the vaccine [xviii], revealing discouraging prospects for successful immunization efforts. An additional problem is the disinformation regarding women in tribal contexts, who are excluded from the possibility of contracting Covid-19 and thus potentially being deprived of immunization [xix]. PEI’s experience with creating awareness and bringing down barriers to acceptance of a vaccine will be useful in implementing the Covid-19 vaccine program.

Importance and Implications

Isolated adaption of either the PEI or EPI may result in less than desired results from the Covid-19 vaccination program. It runs the risk of overburdening the infrastructure and putting the routine immunization programs in competition with the Covid-19 vaccine drive given the limited information, logistical and human resources.

This poses a dangerous risk for polio eradication efforts in Pakistan. A global shift in immunization priorities has also led to lower levels of life-saving vaccine coverage for children for the prevention of dangerous diseases [xx]. The result is the inevitability of a combined surge of Covid-19 and polio cases, overwhelming the existing infrastructure and exacerbating Pakistan’s current health problems.

Therefore, while the existing polio systems of PEI and EPI can serve as the channel for Covid-19 immunization, being already established health programs equipped with physical and information dissemination resources, and established links with federal and provincial decision-makers, they are limited in their capacity to co-deliver two or multiple health interventions at the national level without each other’s assistance.

A viable and effective strategy would then be to utilise an integrated system that benefits from the strengths of the PEI and the EPI systems and can make up for either infrastructure’s shortages, to assist the recovery of the livelihoods of 212 million Pakistanis and the national economy as well, without large disruption in routine immunisation for the country’s growing population.

Recommendations

The immediate integration of Pakistan’s polio infrastructures for the Covid-19 distribution plan (strategized as ‘PEI-EPI synergy’ in the National Emergency Action Plan for Polio Eradication 2020) [xxii] provides a timely opportunity to resolve the infrastructural deficiencies of the national health systems that have long been struggling to meet immunization goals. This approach presents a viable and pragmatic solution aimed at optimising all federal and provincial level resources towards a Covid-19 distribution program.

1

Immediate implementation of the ‘PEI-EPI synergy plan’ for Covid-19

As was done for the eradication of measles, PEI and EPI management teams should be set up for monitoring, data sharing and logistical coordination, such as EPI’s fixed centres and cold storage chain, and PEI’s vehicles for effective immunisation at the provincial & district level.

2

Launch PEI community mobilisation drives

A portion of the PEI’s polio personnel, both health workers and community volunteers, should be trained and mobilised immediately at the community level to increase outreach to households and centre-deficient localities. Here, the role of lady health workers is crucial as part of awareness campaigns to reach families and sensitize their local communities, specifically for the benefit of immobile female communities which are falsely considered to not be at risk of Covid-19 [xxi]. The recruitment of Covid-19 recovered patients as community volunteers may be encouraged to communicate reliable information and build trust in vaccinations.

3

Public-private partnership

To increase the number and reach of fixed facility centres, private sector health facilities such as clinics, hospitals, and labs should be adapted by the joint PEI-EPI operations to achieve better distribution, leading to increased access and vaccine coverage.

4

Map out high-risk communities with PEI’s surveillance systems

To increase the number and reach of fixed facility centres, private sector health facilities such as clinics, hospitals, and labs should be adapted by the joint PEI-EPI operations to achieve better distribution, leading to increased access and vaccine coverage.

5

Address misinformation immediately and synchronize information with all stakeholders

Information campaigns should be launched across all traditional and modern communication channels for maximum inclusivity before the launch of the vaccine. Here, information coordination between federal/provincial governments, the PEI, EPI and private health sector is crucial to be able to deliver coherent and organized messaging to the public. Additionally, the use of local language and influencers needs to be diverse to curb misinformation and build trust in a variety of contexts instead of a homogenous and limited communications strategy.

6

Coordination with Afghanistan’s Polio Network

Introduce the coordinated alignment of Pakistan’s Covid-19 vaccination schedule with Afghanistan’s vaccination schedule, as is strategized under the ongoing Polio Eradication strategy [xxiii]. Data sharing and monitoring between the two neighbouring countries is critical to combat the risk of non-immunized groups of travellers moving across the national borders into high-risk regions of ex-FATA and Balochistan.

This material has been developed by Tabadlab in partnership with DRI. It has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

End Notes

[i] Ikram Junaidi, ‘Pakistan’s allocation for vaccine purchase raised to $250m’, Dawn. 13 Dec 2020.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1595458

[ii] World Health Organization, ‘Contributions of the polio network to the COVID-19 response: turning the challenge into an opportunity for polio transition’. 2020

[iii] Gavi, ‘How is Pakistan maintaining routine immunisation despite the COVID-19 pandemic?’, 5 Aug 2020. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/how-pakistan-maintaining-routine-immunisation-despite-covid-19-pandemic

[iv] GPEI, ‘http://polioeradication.org/polio-today/polio-now/this-week/

[v] Ayesha Raza Farooq. Former SAPM for Polio, Polio Eradication Program, Consultation Dec 2020.

[vi] World Health Organization.

[vii] Rotary, ‘Rotary, polio and COVID-19’. 2020.

https://rotaryoceania.zone/Stories/rotary-polio-and-Covid-19

[viii] Ayesha Raza Farooq.

[ix] World Health Organization.

[x] Consultation.

[xi] Butt, M., Mohammed, R., Butt, E., Butt, S., & Xiang, J. (2020). Why Have Immunization Efforts in Pakistan Failed to Achieve Global Standards of Vaccination Uptake and Infectious Disease Control?. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 111.

[xii] Consultation.

[xiii] Butt, M., Mohammed, R., Butt, E., Butt, S., & Xiang, J.

[xiv] Yasir Waheed. ‘Polio eradication challenges in Pakistan’, Clinical Microbiology and Infection 24.1, 6-7. 2018.

[xv] Butt, M., Mohammed, R., Butt, E., Butt, S., & Xiang, J.

[xvi] Butt, M., Mohammed, R., Butt, E., Butt, S., & Xiang, J.

[xvii] Umar Farooq. ‘Pakistan’s COVID vaccine drive needs antidote to conspiracy theories’. Reuters, Dec 8, 2020.

https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-pakistan-vaccine/pakistans-covid-vaccine-drive-needs-antidote-to-conspiracy-theories-idUSL4N2IK1QL

[xviii] Haroon Hayder. ‘Here’s how many Pakistanis don’t want a Covid-19 Vaccine’. ProPakistani, 12 Dec 2020. https://propakistani.pk/2020/12/15/heres-how-many-pakistanis-dont-want-a-covid-19-vaccine-survey/

[xix] Ginger Johnson, ‘Collecting behavioural insights into COVID-19 in Pakistan’. UNICEF, 6 Dec 2020.

https://blogs.unicef.org/blog/collecting-behavioral-insights-covid-19-pakistan/

[xx] World Health Organization.

[xxi] National Emergency Action Plan for Polio Eradication, Pakistan Polio Eradication Program, 2020.

[xxii] Ginger Johnson.

[xxiii] National Emergency Action Plan for Polio Eradication.

Maryam Mirza has a Master’s in International Politics from SOAS, and a BSc in Economics, Politics and International Relations from Royal Holloway, University of London. Her work involves researching and advising clients on regional and international cooperation for better governance and socio-economic outcomes. She has previously worked on youth development, with high priority for inclusive and integrative approaches, and is particularly interested in political representations in media, and indigenous models and solutions for regional and domestic policy making in the South Asia and MENA regions.