Summary

• Despite recent efforts to digitise health services in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, digital healthcare uptake in Pakistan remains low.

• Low investment in digital health, gaps in health information systems, limited digital access and literacy and limited adoption of payment services are some of the key reasons for low levels of digital health adoption.

• Mainstreaming digital health services can help reduce gaps in the

health workforce, improve timely and professional medical advice especially in rural areas and for females, reduce unnecessary exposure during Covid-19 and improve health information systems.

• To promote digital healthcare, an enabling framework will be required that caters to digital health regulations and standards, creates awareness, improves digital access and literacy especially in rural areas and leverages synergies between public and private sectors.

Identifying the Problem

Pakistan’s success in the Covid-19 healthcare response, from its contact tracing system to pivoting its polio programme’s management structure to support the pandemic, has important implications with regards to public health management. While the health crisis has elevated existing healthcare challenges such as limited infrastructure and capacity, it has also presented new opportunities to bolster alternative delivery channels for healthcare leveraging digital technologies as a means to provide safe, quality care for patients unable to visit hospitals in-person and to ease the strain on healthcare facilities during the pandemic.

Several steps have been taken to prioritise digital health in Pakistan such as self-screening and telehealth initiatives through public-private partnerships with universities, telecommunication providers and healthtech providers. Notably, the government launched the Covid-19 TeleHealth Portal and Yaran-e-Watan platforms to enable online consultations and connect overseas health professionals to institutions in Pakistan that are in need of research expertise and capacity building. Private sector digital health platforms offering teleconsultations have been operational for longer and have gained some recognition but have not been able to achieve scale. Despite recent efforts to digitise services in the face of a national health emergency, digital healthcare uptake in Pakistan remains dismally low.

Why Does the Problem Exist?

The growth of digital healthcare remains stagnant due to multiple factors:

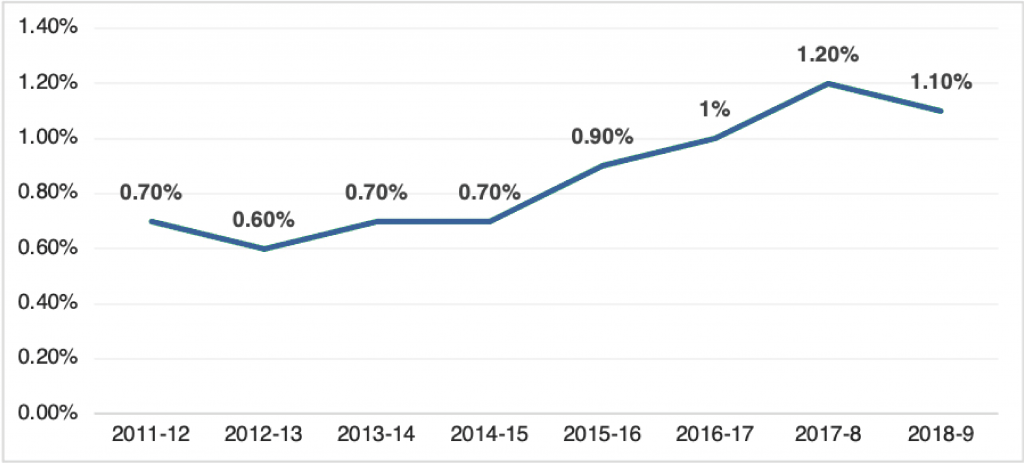

(Source: Tabadlab)

Low Government Spending on Health: In the 2018-19 fiscal year, only 1.1% of the GDP was spent on health expenditures compared to the WHO benchmark of 6%, while a majority of the public health budget is used to finance secondary and tertiary care and leaves less than 20% for preventative and primary healthcare. A low allocation, a disproportionate focus on payroll costs and maintaining physical infrastructure and supplies leaves negligible room for investment in digital health transformations. Limited investment in improving the digital backbone and services in healthcare especially by the public sector is a plausible reason for slow uptake.

Digital Healthcare is not Recognized as a Separate Sector: At the policy level, digital healthcare remains unrecognized as a separate sector within healthcare. Consequently, Pakistan lacks a comprehensive framework for digital health. As such, there are no effective telemedicine regulations or best practices available that would otherwise standardize and empower ongoing initiatives. Another unintended outcome is the large gap in communication between physicians, technology experts and researchers. Insights and evidence from research studies is not integrated in the design and development processes for digital platforms, limiting the effectiveness of digital healthcare solutions from a usability perspective.

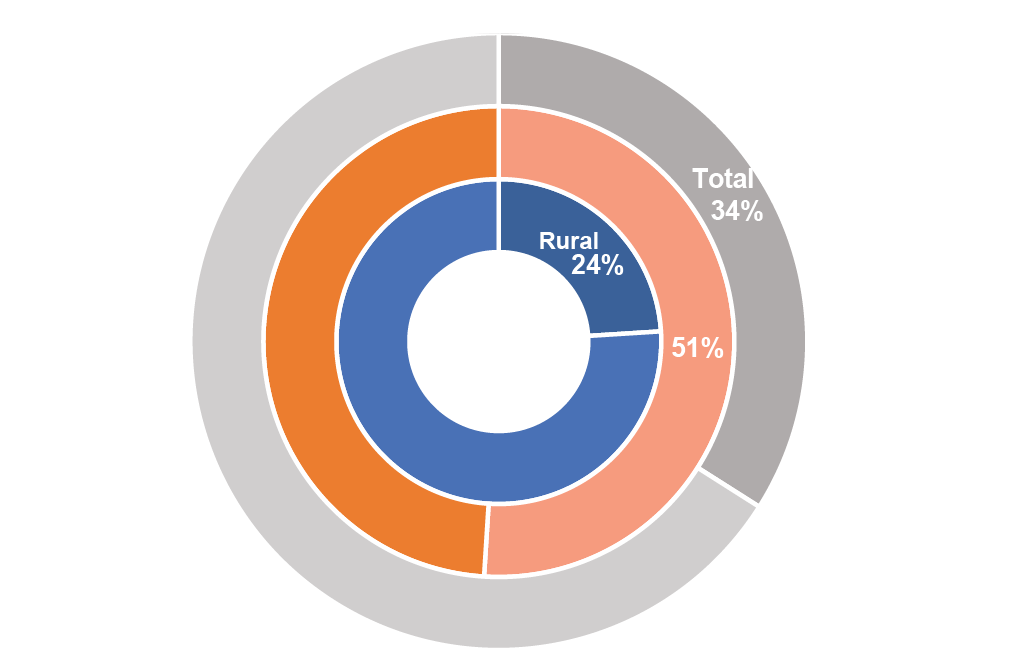

Access in Pakistan (Source: PSLM 2018-19)

Digital Infrastructure and Access: The range of services available to patients is contingent on device ownership, connectivity, network quality and the ability to meaningfully engage with these services. However, Pakistan’s digital landscape is marred by low smartphone usage, low digital literacy and distrust in online platforms. Digital literacy is an impediment to productive digital healthcare experiences, as many patients struggle to operate platforms and transition between audio and video software. Limited smartphone penetration and poor connectivity experience especially in high congestion/poor coverage pockets create barriers for reliance on digital channels for important use-cases like medical advice.

Barriers to Data and Technology: Health information systems for both public and private initiatives suffer from poor systems, fragmentation, data governance for sharing and privacy, and cybersecurity. This results in non-existence of patient data repositories or electronic medical records. Even in case where they exist, access by healthcare workers is a complex problem. Currently, the government uses multiple information systems as opposed to one unified national platform. Data is not published publicly in machine-readable formats. At the national level, a legislative framework for patient records that covers registration, immunization, and disease reporting does not exist. Many recent digital healthcare initiatives also use technology and programming frameworks that are outdated, inhibiting sustainability and effective data analytics. Saving data on local servers can ensure data privacy but comes at a high maintenance and bandwidth cost and thus make interventions harder to scale up [i].

Weak Digital Payment Systems: Low uptake of digital financial services in Pakistan, where only 21% of the population is financially included, is a key barrier to availing online services. The need for credit cards and mobile wallets to make payments is a barrier for utilizing digital health services. Given the low levels of digital and financial literacy, simplifying and opening up the payments value chain for higher adoption will be key to improving usage of online health services.

Importance and Implications

While digitisation of the health sector had already been prioritized in the Digital Pakistan Policy 2018, the Covid-19 pandemic has renewed the country’s focus on digital healthcare. As a developing country with a quickly growing rate of internet and smartphone usage, Pakistan is well-positioned to see a digital health transformation that can mitigate pre-pandemic public health challenges:

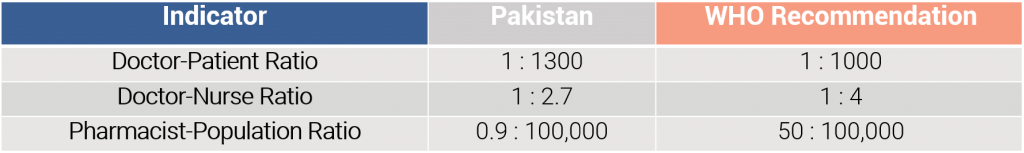

Manage Healthcare Capacity: Pakistan has a shortage of health workforce – doctors, nurses and pharmacists when benchmarked against WHO recommended staffing levels [ii]. Digital healthcare solutions have the potential to enable qualified health professionals to offer services regardless of location and can enable more efficient servicing of patients by optimizing utilization of staff and requirements.

Better Utilization of the Female Healthcare Workforce: Although female students account for 70% of the total student population at medical colleges [iii], only 50% are active in the medical workforce while only 23% are currently registered with the Pakistan Medical & Dental Council. This estimation puts approximately 70,000 to 80,000 qualified doctors who are not part of Pakistan’s health ecosystem. Because household and maternal priorities often require female healthcare professionals to leave their practice, digital platforms allow them to conduct medical practice remotely and at flexible hours, enabling an increased capacity in the health sector.

Safety during Covid-19: During Covid-19, teleconsultations and remote assessments where possible lower the risk involved with visiting healthcare facilities in person. During the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Pakistani healthcare system faced high caseload and burden in many regions with hospitals stretched to capacity while frontline workers had been contracting the virus at high rates. Digital healthcare provides a crucial opportunity to secure healthcare workers and patients during such emergencies.

Improved Access to Health Services including Maternal and Child Health: Although 60% of Pakistanis live in rural areas, healthcare infrastructure is largely concentrated in major cities [iv]. The healthcare workforce shortage that already exists in Pakistan is even higher in rural areas [v]. Medical facilities in rural areas suffer from low staffing capacity that forces residents to travel to expensive tertiary centres in urban areas. The amount of travel required by residents of rural and remote areas to reach these locations result in increased transportation costs, gaps in communication and uncertainty about arrival times. Digital healthcare infrastructure provides a solution to these challenges by reducing travel costs and delivering basic care more swiftly. Disruptions in regular service provision due to Covid-19 coupled with limited female mobility and overburdened health centres can consequently increase the number of gynaecological issues. Helplines and digital services can help reduce the incidence of such cases.

Improve Health Information Systems: Digital health interventions can drastically improve data on health indicators, conditions and outcomes across a range of dimensions covering Covid-19 and non-Covid coverage. System-captured data that is secured and stored can be easily integrated with central health information systems and used for improved monitoring, planning and service delivery improvements.

Recommendations

1

Recognize Digital Healthcare as an Individual Sector

In order to ensure quality services, digital healthcare needs to be recognized as an individual sector within healthcare. Additionally, a legal and ethical policy framework for digital healthcare that outlines best practices for telemedicine and health information should be prioritized. An efficient healthcare service model will not be possible if it is not recognised and supported by policymakers.

2

Collaboration Between Actors

Healthcare providers must unify with other actors in the ecosystem to make digital healthcare equitable for those who lack digital access. Collaboration between stakeholders such as researchers, technology professionals, frontline workers, entrepreneurs and policymakers is key to guaranteeing that all aspects of digital healthcare – technology, quality of care, regulation and service standards, etc. – are synchronised for optimal experience.

3

Leverage Public Private Partnerships

The constraints on public health budgets can be mitigated through public private partnerships that leverage the capacity, innovation, and financial resources of private sector players. Preventative care, vaccination structures, disease surveillance and research for existing platforms can be scaled up through PPPs with healthcare start-ups. Healthcare start-ups that focus on digital services can be facilitated by a HealthTech incubator and/or accelerator.

4

Promote Awareness of Benefits of Digital Healthcare Systems

Mistrust of online platforms and unfamiliarity with digital healthcare requires a mass awareness campaign targeted to improve patient readiness. Digital literacy and adoption can be substantially improved by increasing awareness about the benefits of digital healthcare through avenues such as promotion campaigns. Success stories from digital health interventions during the pandemic should be publicized in order to communicate the potential benefits of telemedicine and online health platforms.

5

Reform Health Technology and Information Systems

Effectiveness of digital healthcare policies cannot be guaranteed if they are not backed by evidence and data. A legislative framework for health information that mandates national and regional health registries is required to ensure quality of care. Federal and provincial layers of the government should mandate open data standards that enables seamless access to patient records and ensures data accuracy and standardisation. Technological reform that improves cybersecurity, safeguards patient privacy, and optimizes costs and technical efficiency can be incentivized by encouraging private actors to innovate through incubator hackathons or regulatory sandboxes.

6

Improve Digital Access

Bridging the rural-urban divide and providing digital care to Pakistan’s overlooked citizens will require expanding digital access. Policies that improve coverage, connectivity and experience should be prioritized especially for rural areas. The Universal Service Fund (USF) is a mechanism designed to improve Internet infrastructure in far-flung areas that are otherwise unprofitable. However, much of the funds allocated to the USF have remained inaccessible. The government should also focus on improving affordability of mobile phones and telecom services by rationalizing mobile sector taxation.

This material has been developed by Tabadlab in partnership with DRI. It has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

End Notes

[i] Kazi, A. M., Qazi, S. A., Ahsan, N., Khawaja, S., Sameen, F., Saqib, M., Khan Mughal, M. A., Wajidali, Z., Ali, S., Ahmed, R. M., Kalimuddin, H., Rauf, Y., Mahmood, F., Zafar, S., Abbasi, T. A., Khoumbati, K. U., Abbasi, M. A., & Stergioulas, L. K. (2020). Current Challenges of Digital Health Interventions in Pakistan: Mixed Methods Analysis. Journal of medical Internet research, 22(9), e21691.

https://doi.org/10.2196/21691

[ii] Chaudhry, M.A. & Khan, A. (2020, July 14). An Actionable Agenda for Achieving Universal Health Coverage in Pakistan. Tabadlab.

https://www.tabadlab.com/shaping-21st-century-public-health-in-pakistan-an-actionable-agenda-forachieving-universal-health-coverage/

[iii] Doctors-in-Law: The Case of Pakistan’s Missing Female Doctors. Academia. (2020, February 25). Academia.

https://academiamag.com/doctors-in-law-the-case-of-pakistans-missing-female-doctors/

[iv] Chaudhry, M.A. & Khan, A.

[v] Chaudhry, M.A. & Khan, A.

Aliza Amin is a Policy Associate at Tabadlab’s Centre for Digital Transformation, where she is responsible for research and analysis of the policy landscape, evolution of digital ecosystems and advisory for transformations. She has been a researcher at Wellesley College and MIT and has worked with non-profit organisations in Pakistan, Morocco and the United States. Aliza graduated from Wellesley College in 2020.