Summary

• The Covid-19 pandemic has brought the digital agenda to the front. While the digital transformation agenda in Pakistan is not new, the pandemic has infused a new and fresh urgency into the question of how Pakistanis connect with each other.

• Digital access continues to remain out of reach for more than half of the country. Moreover, Pakistan suffers from one of the largest digital gender gaps in the world that poses particular challenges in certain geographic areas.

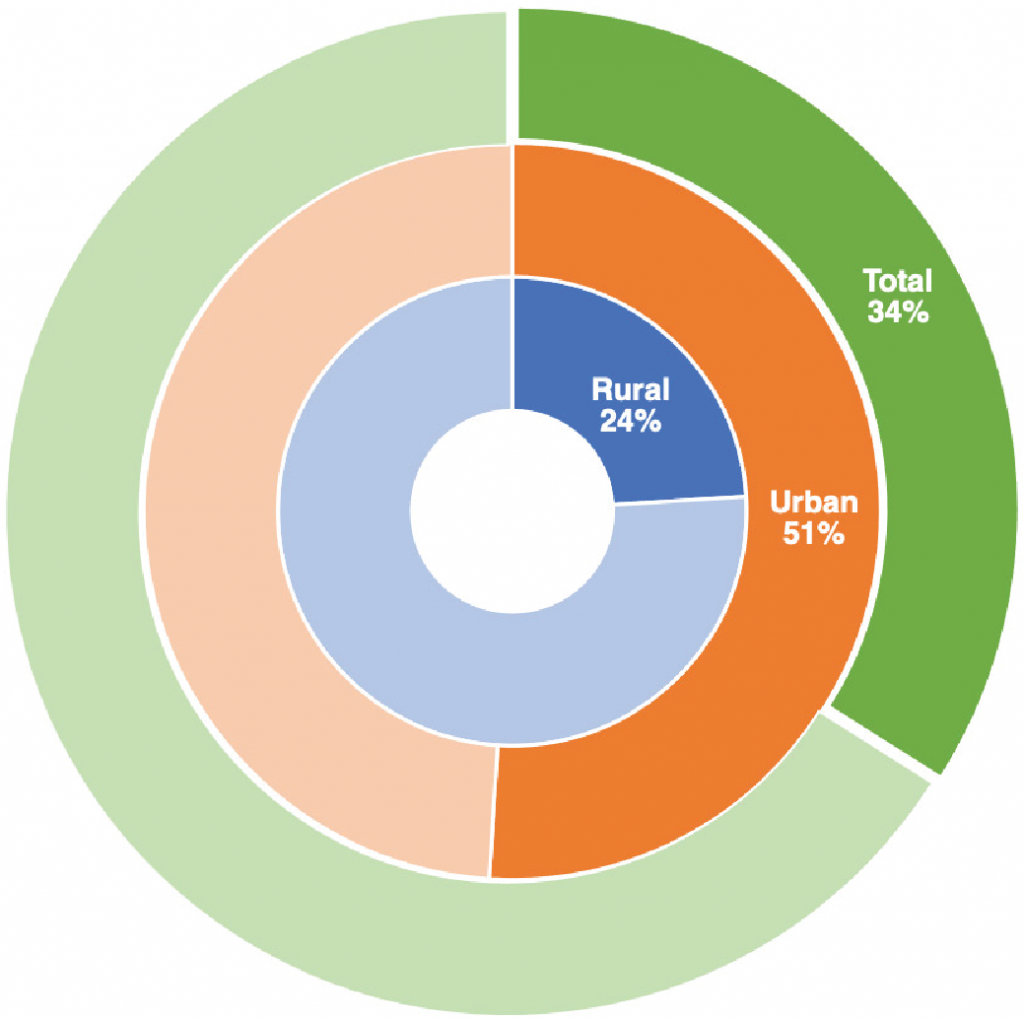

• Despite making up more than 60% of the population, only 24% of rural households have access to the Internet. Poor network quality, limited affordability, and literacy and cultural barriers pose challenges to digital access and device ownership among this section and contribute to the rural-urban gap.

• According to the International Telecommunication Union, a 10% increase in mobile broadband penetration can generate a 1.8%

increase in GDP growth for developing countries [i]. Digital readiness is a powerful tool for achieving SDGs and can stimulate areas such as finance, education, health, agriculture, and gender inclusion.

• Key areas of policy that require immediate attention include taxation, spectrum allocation and incentive to reach remote areas. From the demand side, low levels of digital literacy, negligible perceived advantages of adopting digital services, and the low affordability of smartphones and internet services, serve as major constraints.

• Progress in expansion of digital access requires a multi-stakeholder engagement process and consensus building to effect policy change. Given that some policy changes may require short term compromises to achieve long term access goals, clear policy direction and intent from the top is required in addition to clear ownership to drive the agenda.

Identifying the Problem

In December 2019, the Digital Pakistan Vision was launched as a government initiative that aimed to expand digital access, the equitable distribution of technology and online resources, and enable digital growth. Months later, the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic laid bare how digital access is essential to both the wellbeing of citizens and the economy. Schools and companies have shifted online to ensure safety and prevent transmission of the virus, while healthcare facilities, banks, and other essential services continue to seek digitally enabled remote solutions. However, the Covid-19 experience for millions of Pakistanis who did not have digital access was completely different; the digital divide was never this prominent for those who could not access online learning resources or go to work, among many other things.

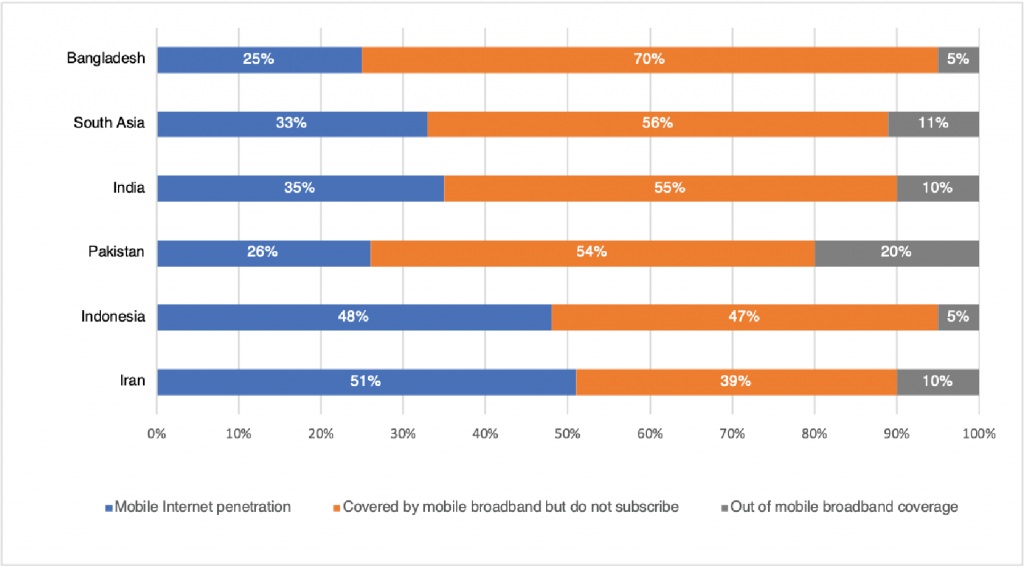

(Source: GSMA Intelligence)

Digital access continues to remain out of reach for more than half of the country. The Inclusive Internet Index 2020 has ranked Pakistan 76th out of 100 countries on digital inclusivity, behind neighbours India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. Challenges to universal digital access are characterised by four key issues:

- A rural-urban digital divide in which at least 65% of Pakistan’s population live in areas with little to no internet access [ii].

- Device ownership remains limited as only 14% of the population own smartphones or computers.

- Pakistan suffers from a sizeable digital gender gap that poses particular challenges in Balochistan, KP, and interior Sindh and excludes women from participating in society.

- Low digital literacy that inhibits citizens from fully utilising the benefits of the digital sphere and gaining necessary twenty-first-century skills

Why does the problem exist?

Several barriers hinder universal digital access in Pakistan:

Limited Affordability: Currently, the total cost of mobile ownership for low and medium consumption baskets does not meet the UN Broadband Commission’s “1 for 2” affordability target, in which one gigabyte of data costs less than 2% of an individual’s monthly income [iii]. Telecom services are taxed strictly; in some areas of Pakistan, the telecoms general sales tax is as high as 19.5% [iv] and affect the retail prices for mobile devices, SIM cards, and data usage, which especially impact income groups in the lower percentiles [v]. The upfront cost of mobile devices also represents less affordability for lower-income Pakistanis who are not able to pay in instalments.

Poor Network Quality: Compared to several other neighbouring countries and Asian markets, Pakistan has assigned significantly less spectrum and Internet bandwidth to network operators [vi]. Low spectrum allocation and high license fees prevent operators from improving internet services, especially in remote and rural regions, and hamper digital access.

Literacy and Cultural Barriers: To meaningfully engage with the Internet, the ability to read fluent English or Roman Urdu, the languages of most of Pakistan’s online spaces, is necessary. However, Pakistan’s literacy rates fare poorly compared to other low middle-income countries with just over half of the population knowing how to read and write [vii]. Cultural barriers, such as conservative understandings of the Internet and a lack of content in locally relevant languages, also present an impediment to digital inclusivity and impact consumer readiness [viii].

Gender: Pakistan faces one of the largest digital gender divides in the world due to issues of cultural restrictions, which pose particular challenges in Balochistan, KP, and interior Sindh. Socioeconomic conditions mean that families are less willing to invest in devices for women or allow them digital privacy compared to their male counterparts [ix]. Spaces that originally provided digital resources such as work and school are no longer accessible to women during lockdowns. Additionally, cybercrimes such as online harassment and information misuse present great risks to women and their digital experiences. Such occurrences only amplify the perception that Internet access poses a threat and consequently increase restrictions for women.

Importance and Implications

While digital access had already been recognized as an enabler for growth and innovation, the COVID-19 crisis has demonstrated that digitization is now central to the future. According to the International Telecommunication Union, a 10% increase in mobile broadband penetration can generate a 1.8% increase in GDP growth for developing countries [x]. Digital readiness is a powerful tool for achieving SDGs and can stimulate five key areas:

Education: Covid-19 has particularly brought digital access’s role in education and skills to the forefront. In March, thousands of schools transitioned to online learning, while the government partnered with tech companies to provide distance learning resources. Due to the uncertain nature of the pandemic, digital access has become paramount to ensuring learning continuity. The pandemic has also underscored the opportunities available for technology to not only support the process of ensuring quality education in developing countries but also to be leveraged to solve existing educational challenges such as a large number of out of school children in Pakistan.

Healthcare: Over half of Pakistanis do not have access to basic healthcare services. During the Covid-19 crisis, the healthcare sector launched several smart apps after millions of Pakistanis lost access to vital health information and were unable to physically visit medical centres. The crisis reinforced the opportunity for telemedicine and remote diagnostics to provide healthcare for citizens in remote and rural areas who live far from hospitals. Enabling and thus documenting online healthcare solutions can also increase data collection and accordingly improve overall healthcare programming.

(Source: PSLM 2018-19) (Source: GSMA Intelligence)

Financial inclusion: During the pandemic, Internet banking transactions grew at a rate of 64%, while mobile transactions more than doubled since last year [xi] after in-person financial services became unsafe. In a developing country, digital financial services can accelerate financial inclusion by delivering services at an efficient rate, increasing financial documentation, and banking millions of unbanked citizens. Broadening Pakistan’s digital financial market can create 4 million jobs, increase deposits in circulation by $250 billion, and increase the GDP by 7% [xii].

Agriculture: Agriculture is a key sector, that contributes to 20% of Pakistan’s GDP and employs almost 40% of the workforce. However, so far, efforts at digitizing the sector have been limited despite significant opportunity to improve value chain and leverage digital tools to improve capacity and enhance productivity. While over 90% of agricultural workers are from rural areas, only 24% of the rural population has access to the Internet [xiii].

Inclusion: According to the UN, domestic violence has substantially increased during Covid-19 lockdowns, due to which women no longer have access to physical channels for help. Digital resources provide a way for women to not only remain employed or in school, but to also receive emergency assistance and find inclusive spaces. As a country in which more than half the population is under 30 [xiv], Pakistan can digitally expand at an unprecedented rate and reap economic benefits. However, as the economy and essential services become more reliant on digital infrastructure, those on the margins of access will struggle to keep up. A Covid-19 world that is digitalising at an unprecedented pace risks exacerbating inequalities in education, healthcare, and overall living standards and leaving millions of citizens behind.

Recommendations

1

Stakeholder Engagement

Progress in the expansion of digital access requires a multi-stakeholder engagement process and consensus building to effect policy change. Given that some policy changes may require let’s say a cut in revenue sources in the near to medium term, effecting the same with a long-term view is not possible without a clear policy direction and intent from the top in addition to clear ownership to drive the agenda.

2

Prioritize Rural Areas for Digital Expansion

Bridging the rural-urban divide and providing access to Pakistan’s overlooked citizens will require an upgrade in digital infrastructure. Policies that lower the cost of network deployment should be designed. The Universal Service Fund (USF) is a mechanism designed to improve Internet infrastructure in far-flung areas that are otherwise unprofitable. However, much of the funds allocated to the USF have remained inaccessible. The Jio Effect case study, which expanded digital access by making 4G Internet available for free before charging citizens once Internet subscriptions had increased substantially [xv] , can also be replicated via public-private partnerships and incentives.

3

Bridge the Gender Divide

An equitable future for women and girls cannot be secured without first securing digital access. The government should collaborate with on-ground NGOs to implement a data collection and monitoring initiative that uses gender-disaggregated data to design targeted interventions. The Ministry of Human Rights can partner with telcos and civil society networks to design awareness campaigns that encourage digital access for women. An effective digital harassment policy is also necessary to ensure women’s online safety—this can be achieved by collaborating with digital rights NGOs.

4

Improve Affordability of Telecom Services

Due to limited laptop and tablet ownership, mobile is the primary medium for Internet access in Pakistan. The government should therefore focus on enabling the mobile phone ecosystem by reforming mobile sector taxation in a manner that increases the affordability of telecom services and generates tax revenue in the long term. A favourable tax regime has the potential to raise mobile broadband penetration, encourage sectoral innovation, and accordingly increase GDP. Moreover, incentives for local manufacturing of smartphones may also be considered.

5

Develop a Spectrum Policy

The government and PTA should collaborate and develop a robust spectrum strategy and licensing process so that operators can plan investments accordingly. Allocation of sufficient spectrum should be ensured for operators to facilitate improved coverage and faster speeds, with a particular focus on the spectrum that enables deployment of mobile broadband networks in rural areas with low population density.

6

Launch an Awareness Campaign

A behavioural transformation is requisite to increasing consumer demand. Digital literacy and adoption can be substantially improved by increasing awareness about the benefits of digital services through avenues such as telco campaigns. The new awareness of digital technology’s role in a COVID-19 world can also be leveraged to both increase availability of locally relevant content and to encourage families with conservative understandings of the Internet to allow children and female members access.

This material has been developed by Tabadlab in partnership with DRI. It has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

End Notes

[i] ITU. (2019). The economic contribution of broadband, digitization, and ICT regulation: Econometric modelling for the America.

http://handle.itu.int/11.1002/pub/811e77bf-en

[ii] Raza, A. (2020, October 13). COVID-19 Reveals the Divide in Internet Access in Pakistan. Borgen Magazine. https://www.borgenmagazine.com/internet-access-in-pakistan/

[iii] Robinson, J. (2020). Pakistan: progressing towards a fully fledged digital economy. GSMA. https://www.gsma.com/asia-pacific/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/24253-Pakistan-report-updates-LR.pdf

[iv] Robinson, J.

[v] Robinson, J.

[vi] Robinson, J.

[vii] UNESCO Institute of Statistics. (2020). [Education and Literacy Statistics for Pakistan]. http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/pk?theme=education-and-literacy

[viii] GSMA. (2020). The Mobile Economy 2020. https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/GSMA_MobileEconomy2020_Global.pdf

[ix] Ayub, M. H. (2020, June 8). Digital Gender Divide: Internet is essential for women to access important information.Digital Rights Monitor.

https://www.digitalrightsmonitor.pk/digital-gender-divide-internet-is-essential-for-women-to-access-important-information/

[x] ITU.

[xi] State Bank of Pakistan. (2020). Annual Report 2019-2020: The State of Pakistan’s Economy. https://www.sbp.org.pk/reports/annual/arFY20/Complete.pdf

[xii] McKinsey Global Institute. (2016, September). Digital Finance For All: Powering Inclusive Growth in Emerging Economies. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/Employment%20and%20Growth/How%20digital%20finance%20could%20boost%20growth%20in%20emerging%20economies/MGI-Digital-Finance-For-All-Executive-summary-September-2016.ashx

[xiii] Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. (2018, December). Labour Force Survey 2017-8. http://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files//Labour%20Force/publications/lfs2017_18/Annual%20Report%20of%20LFS%202017-18.pdf

[xiv] Ahmad, S. (2018, July 24). Unleashing the potential of a young Pakistan. UNDP. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/unleashing-potential-young-pakistan

[xv] Ghosh, Shona. (2020, July 14). How the ‘Jio effect’ brought millions of Indians online and is reshaping Silicon Valley and the internet.

https://www.businessinsider.com/reliance-jio-millions-of-indians-online-reshaped-internet-2019-8

Aliza Amin is a Policy Associate at Tabadlab’s Centre for Digital Transformation, where she is responsible for research and analysis of the policy landscape, evolution of digital ecosystems and advisory for transformations. She has been a researcher at Wellesley College and MIT and has worked with non-profit organisations in Pakistan, Morocco and the United States. Aliza graduated from Wellesley College in 2020.